Introduction

Despite the large-scale secularization in many Western European countries, scholars have pointed to the enduring importance of religion in the political sphere (Marcinkiewicz and Dassonneville, Reference Marcinkiewicz and Dassonneville2022; Minkenberg, Reference Minkenberg and Rydgren2018). Although collective religiosity of Christians – e.g., church membership and service attendance – is declining, religiosity on the individual level is often discussed and at times found to be associated with anti-pluralistic attitudes and outgroup-hostility, such as nativism (Arzheimer and Carter, Reference Arzheimer and Carter2009; Immerzeel et al., Reference Immerzeel, Jaspers and Lubbers2013; Marcinkiewicz and Dassonneville, Reference Marcinkiewicz and Dassonneville2022; Montgomery and Winter, Reference Montgomery and Winter2015; Siegers and Jedinger, Reference Siegers and Jedinger2021). Across a range of studies, however, the findings are inconsistent and sometimes even contradictory ranging from a mitigating (Marcinkiewicz and Dassonneville, Reference Marcinkiewicz and Dassonneville2022) to a reinforcing (Immerzeel et al., Reference Immerzeel, Jaspers and Lubbers2013; Montgomery and Winter, Reference Montgomery and Winter2015) association—or report no evidence at all (Arzheimer and Carter, Reference Arzheimer and Carter2009). Recent research suggests the role of contextual differences in the impact of religiosity on nativism (Marcinkiewicz and Dassonneville, Reference Marcinkiewicz and Dassonneville2022; Xia, Reference Xia2021). Yet, we lack insights on relevant contextual factors like the strength and visibility of actors that instrumentalize religion to reinforce nativist sentiments. The most prominent actors in that regard are populist radical right parties (PRRPs) that politicize Christianity to promote their right-wing stances and mobilize voters (Minkenberg, Reference Minkenberg and Rydgren2018; Schwörer and Romero-Vidal, Reference Schwörer and Romero-Vidal2020). In regions with a Christian-shaped heritage, PRRPs build their nativist discourse on the construction of a threat to the “Christian West” that must be defended. By doing so, these parties aim to appeal to potential voters’ perceptions of threat, positioning themselves as saviors of the alleged native cultural identity (Marzouki et al., Reference Marzouki, McDonnell and Roy2016; Mudde, Reference Mudde2019). In general, a party’s entrance into parliament comes with political legitimacy and access to resources (Abou-Chadi and Krause, Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2020; Dinas et al., Reference Dinas, Riera and Roussias2015). While populist radical right success is not an entirely new phenomenon, these parties recently gained not only parliamentary representation but also access to office (Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, de Lange and Rooduijn2016; Minkenberg, Reference Minkenberg2017; Mudde, Reference Mudde2013; Mudde, Reference Mudde2019). This might not only legitimize the positions of PRRPs, leading to a higher social acceptance of radical right-wing attitudes (Bohman, Reference Bohman2011; Valentim, Reference Valentim2021), but the link between their representation and their shaping of public opinion might then become much more relevant (Bennett, Reference Bennett1990; Hopmann et al., Reference Hopmann, Christian Elmelund-Præstekær, Vliegenthart and de Vreese2012; Van der Brug and Berkhout, Reference Harteveld, Wouter van der Brug and Kokkonen2015). Since the politicization of Christianity appears pivotal to the contemporary right-wing populist agenda, the establishment of PRRPs within the political arena is likely to be relevant to the impact of religiosity on nativism.

In this study, I hence address the relationship between religion and nativism by providing answers to the following research question: Does PRRPs’ participation in government influence the impact of individual religiosity on nativism? I argue, first, that more religious Christians are likely to have a stronger tendency toward nativism and expect, second, that the government participation of PRRPs reinforces this effect. This can be explained by the relative attention and visibility of government communication vis-à-vis the communication of other parties, resulting in a higher salience of their messages that politicize Christianity and emphasize the need of defending an alleged Christian heritage against the threat of immigration and foreigners.

To test these theoretical expectations, I conduct a cross-country analysis using data from the Joint European Values Study/World Values Survey (EVS/WVS, 2022) covering the period from 2017 to 2022. In this paper, I provide evidence for an association between Christian religiosity and nativism. Findings suggest that Christians are more likely to tend to nativist attitudes when they hold higher levels of religiosity. Additionally, the analysis highlights differences in the effects of religious components, with religious beliefs appearing to be the key factor driving this association. However, the relationship between religiosity and nativism is not strengthened by populist radical right participation in government. Overall, these results contribute to existing literature by further supporting studies that report a reinforcing religiosity–nativism linkage (Montgomery and Winter, Reference Montgomery and Winter2015; Immerzeel et al., Reference Immerzeel, Jaspers and Lubbers2013), particularly those emphasizing the role of beliefs (Immerzeel et al., Reference Immerzeel, Jaspers and Lubbers2013). Thus, this study underscores the conclusion that the religiosity of Christians might indeed be related to attitudes that oppose a plural society.

Christian religiosity and nativism: the state of the art

In recent years, the concept of nativism has been established and shaped as the constituent element of the populist radical right (Mudde, Reference Mudde2007). As a combination of xenophobia and nationalism, the nativist ideology “holds that states should be inhabited exclusively by members of the native group (‘the nation’) and that non-native elements (persons or ideas) are fundamentally threatening to the homogeneous nation-state” (Mudde, Reference Mudde2007, 19). The differentiation between an ingroup and an outgroup is built around cultural characteristics rather than biological racism, thus promoting the ethnopluralist idea of ethnic groups not being superior or inferior to each other but should remain separated. Rejecting cultural heterogeneity then serves to prevent the amalgamation of allegedly pure cultures (Mudde, Reference Mudde2007; Reference Mudde2019).

Research on nativism, particularly in Europe, is tightly interwoven with research on the contemporary populist radical right, as anti-immigrant stances were identified as the most important predictor for their electoral success (Arzheimer, Reference Arzheimer and Rydgren2018). In this way, previous work deals with the determinants of the surge of this party family, looking at contextual factors (Arzheimer, Reference Arzheimer2009; Hays et al., Reference Hays, Lim and Spoon2019), parties’ positions (Akkerman, Reference Akkerman2015; Lewandowsky et al., Reference Lewandowsky, Giebler and Wagner2016; Rovny, Reference Rovny2013), their communication strategies (Albertazzi and Bonansinga, Reference Albertazzi and Bonansinga2023; Borbáth and Gessler, Reference Borbáth and Gessler2023; Popivanov, Reference Popivanov2022; Schwörer and Romero-Vidal, Reference Schwörer and Romero-Vidal2020; Wirz et al., Reference Wirz, Martin Wettstein, Philipp Müller, Ernst, Esser and Wirth2018) and, most prominently, their electorate (Arzheimer, Reference Arzheimer and Rydgren2018; Brils et al., Reference Brils, Muis and Gaidytė2022; Harteveld et al., Reference Harteveld, Wouter van der Brug and Kokkonen2015; Van der Brug et al., Reference van der Brug, Fennema and Tillie2000).

When it comes to the role of Christian religion in explaining populist radical right voting, researchers have found some inconsistency – noting, however, predominantly a rather marginal role of Christian religiosity in PRRPs’ electorate in Europe (Arzheimer and Carter, Reference Arzheimer and Carter2009; Dilling, Reference Dilling2018; Immerzeel et al., Reference Immerzeel, Jaspers and Lubbers2013; Lubbers et al., Reference Lubbers, Gijsberts and Scheepers2002; Marcinkiewicz and Dassonneville, Reference Marcinkiewicz and Dassonneville2022; Montgomery and Winter, Reference Montgomery and Winter2015; Norris, Reference Norris2005; Stankov and Živković, Reference Stankov and Živković2022; Van der Brug et al., Reference van der Brug, Fennema and Tillie2000; Van der Brug and Fennema 2003)Footnote 1 , and an ambivalent impact of Christian religiosity on nativist attitudes (Arzheimer and Carter, Reference Arzheimer and Carter2009; Immerzeel et al., Reference Immerzeel, Jaspers and Lubbers2013; Montgomery and Winter, Reference Montgomery and Winter2015; Marcinkiewicz and Dassonneville, Reference Marcinkiewicz and Dassonneville2022; Siegers and Jedinger, Reference Siegers and Jedinger2021). Arzheimer and Carter (Reference Arzheimer and Carter2009) do not find a significant link between the latent construct of composite religiosity components and anti-immigrant attitudes in eight Western European countries with data from the 2002 European Social Survey (ESS). Montgomery and Winter (Reference Montgomery and Winter2015) follow Arzheimer and Carter’s multidimensional operationalization of Christian religiosity, employing an aggregate index with self-evaluated intensity of religiousness, frequency of church attendance, and private prayer. However, in contrast to Arzheimer and Carter’s results, they report a positive association between religiosity measured by the above-mentioned index, and nativism for a similar sample of Western European countries, but also including Poland, Slovakia, and Hungary. Immerzeel et al. (Reference Immerzeel, Jaspers and Lubbers2013) use the 2008 European Values Study to examine the impact of service attendance, religious particularism, and doctrinal beliefs on anti-immigrant attitudes in a differentiated way and find a negative association in six out of seven Western European countries in terms of the frequency of service attendance. When operationalizing religiosity with church attendance using more recent 2016 ESS data, Marcinkiewicz and Dassonneville (Reference Marcinkiewicz and Dassonneville2022) also point to an average negative association for fifteen Western and Eastern European countries. This indicates that Christian religious factors appear to be differently tied to nativism. Research in the U.S. context supports this, with such an association being relevant for religious belonging, but less so for frequency of religious behavior (Whitehead and Perry, Reference Whitehead and Perry2020). Their respective influence must therefore be considered. This is particularly important because, according to previous sociological work, different components of religiosity are not necessarily linked, as in the phenomenon of “believing without belonging” observed by Grace Davie (Reference Davie1990) for the United Kingdom. Thus, divergent approaches to conceptualization and empirical implementation may explain why Arzheimer and Carter’s pioneering work identifies no effect while others apparently point to correlations. Montgomery and Winter, for example, do not integrate the dimension of belonging in their religiosity index. Furthermore, findings reported by Immerzeel et al. (Reference Immerzeel, Jaspers and Lubbers2013) imply that orthodox Christian believers are likely to hold stronger anti-immigrant sentiments compared to other, more tolerant ones. However, they only demonstrate this for a limited set of three countries. This effect may be explained by the operationalization based on belief content instead of merely self-rated intensity of religiousness. The case selection itself may also be a relevant factor. For the above-mentioned studies in the European context, the sample is limited to national contexts in which a populist radical right party was running for election.

To be clear, high levels of religiosity in general are sometimes discussed as being associated with conservative and traditional views and thus with exclusionary tendencies. In Europe and Latin America, however, such views are unlikely to lead to support for right-wing stances among Muslims, for example. This is because Muslims currently represent the primary outgroup targeted by PRRPs. In analyzing the religiosity-nativism nexus, it is necessary to focus on the alleged ingroup of PRRPs. Given the study’s regional context, this is the religiosity of Christians.

Research on nativism, however, also presents the role of Christianity as a cultural marker against Islam, without implying religious identity (Arzheimer and Carter, Reference Arzheimer and Carter2009; Cremer, Reference Cremer2023; Marzouki et al., Reference Marzouki, McDonnell and Roy2016). Right-wing actors who claim to defend the religious identity of the autochthonous people (Froio, Reference Froio2018; Stankov and Živković, Reference Marcinkiewicz and Dassonneville2022) presumably do so because the rejection of immigration is particularly well argued through Christianity as part of national identity (Mudde, Reference Mudde2019; Storm, Reference Storm2011). Accordingly, identification with Christianity does not necessarily require individual religiosity (Minkenberg, Reference Minkenberg and Rydgren2018; Storm, Reference Storm2011), and so individual religiosity in this case is not necessarily related to levels of nativism.

Despite these valuable initial insights on Christian religiosity and nativism, the connection has not yet been fully clarified. Several of these previous studies hint at the effectiveness of contextual factors, for example, that the presence of a Christian-democratic party distracts religious Christians from voting for the populist radical right. Moreover, Marcinkiewicz and Dassonneville (Reference Marcinkiewicz and Dassonneville2022) find that the religiosity–PRR voting association varies most notably across Western and Eastern European countries. Thus, while research to date suggests that the religiosity’s effect on nativism might be context-dependent, my study adds to this existing literature by considering that the government participation of PRRPs might have an influence on the religiosity–nativism nexus. This is, firstly, because we know from literature that a political party that enters the national parliament gains political legitimacy and access to valuable resources (Abou-Chadi and Krause, Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2020; Dinas et al., Reference Dinas, Riera and Roussias2015). Their parliamentary presence thus affects how voters can be addressed, and in this way, as Valentim (Reference Valentim2021) states, the success of PRRPs may moreover affect public opinion. By this, populist radical right’s rise to parliament may also legitimize the party’s positions, leading to a higher social acceptance of radical right-wing attitudes (Bohman, Reference Bohman2011; Valentim, Reference Valentim2021). Furthermore, previous work shows that PRRPs may raise the salience of specific issues (Akkerman, Reference Akkerman2015), while other parties also adopt their positions (Abou-Chadi and Krause, Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2020). However, so far existing research on populist radical right representation’s impact on public opinion does not provide consistent answers. While there is no evidence that their parliamentary presence influences attitudes towards migrants (Bohman and Hjerm, Reference Bohman and Hjerm2016) or minorities (Dunn and Singh, Reference Dunn and Singh2011), Bischof and Wagner (Reference Bischof and Wagner2019) find that voters do indeed become ideologically polarized when the populist radical right enters parliament. Secondly, when political parties are in power, the linkage between a party’s representation and its shaping of opinions and attitudes in society plays a much greater role than when they are merely present in parliament. Previous research shows that rise to office is not only clearly linked to high levels of political and institutional strength but also to a greater visibility compared to opposition parties (Bennett, Reference Bennett1990; Hopmann et al., Reference Hopmann, Christian Elmelund-Præstekær, Vliegenthart and de Vreese2012; Van der Brug and Berkhout, Reference Harteveld, Wouter van der Brug and Kokkonen2015).

Since, most prominently, PRRPs instrumentalize religion to reinforce nativist sentiments, this paper accounts for those parties’ government participation to explain how Christian religiosity is linked to nativism.

Theory

Does PRRPs’ participation in government influence the impact of individual religiosity on nativism? As previous studies suggest, the potential effect of Christian religiosity on nativism appears at first to be ambivalent. This ambivalence requires explanation. Theoretically, the religiosity–nativism nexus can be addressed using explanatory approaches from social psychological research on prejudice (see above all Allport, Reference Allport1966). Accordingly, the paradoxical character of religiosity can be elucidated in that religion can be positively related to nativism due to its role as a cultural demarcation feature and negatively related due to its unifying character (Arzheimer and Carter, Reference Arzheimer and Carter2009; Immerzeel et al., Reference Immerzeel, Jaspers and Lubbers2013; Marcinkiewicz and Dassonneville, Reference Marcinkiewicz and Dassonneville2022). The first mechanism mentioned taps into the group dynamic of social identity (Tajfel, Reference Tajfel1982; Tajfel and Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, W and WG1986). Presuming that group affiliation is substantial for individuals’ self-esteem, the construction of an ingroup defined as positive and in distinction to an outgroup often evokes degradation to maintain group status. Despite theoretical explanations and empirical evidence for both directions, I argue that Christian religiosity reinforces nativism. This is due to PRRPs’ mobilization based on stances where hostility towards migration is framed in religious terms, pointing to the Christian heritage of a country that is allegedly threatened by the influx of non-Christian foreigners. It can be assumed that these parties aim to attract potential voters by referencing Christianity to convince them of their populist radical right agenda.

In light of the group dynamic processes described above, I expect religiosity Footnote 2 to be linked to ideological elements of nativism. First, individual religiosity could come with formal affiliation. Religious belonging, in the sense that formal Christians are already committed to a Christian faith community, may serve as a cultural marker to distinguish between a supposedly Christian ingroup and a foreign outgroup. Second, strongly internalized and exclusivist religious beliefs may strengthen group identification. Such beliefs are often marked by doctrinal interpretations and claims to absolute truth. Third, religious behavior, whether through frequent church attendance, private prayer, or participation in social activities, may reinforce ingroup attachment, particularly when it comes to involvement in a homogeneous cohesive faith community.

As a result of intergroup comparison, Christians should be more susceptible to exclusion and degradation, as those dynamics stabilize their group status, further strengthening ingroup identification (cf. theoretical assumptions of social identity, Tajfel, Reference Tajfel1982; Tajfel and Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, W and WG1986). The described mechanism overlaps with the nativist narrative of a culturally homogeneous nation threatened by foreign elements that must be preserved. While formally, there is no group hierarchization, the enhancement of the native ingroup often leads to a derogative stance on non-natives at the same time. Christians, especially those with intense community involvement and strongly internalized beliefs, should show a strong nativist tendency.

Hypothesis 1 The more religious Christians are, the more they tend to have nativist attitudes.

Further on, this is where I take up the central mechanism of this study. I expect the impact of Christian religiosity on nativist attitude patterns to be stronger in countries where PRRPs are in power. As previous work shows, PRRPs adopt political messages with religious connotations more prominently in their communication compared to other parties (Schwörer and Romero-Vidal, Reference Schwörer and Romero-Vidal2020; Rosenberg, Reference Rosenberg2023).Footnote 3 Differences in the salience of references to Muslims as well as to Christians by several European parties are statistically significant. In addition, PRRPs link the most negative evaluation of Islam with the most positive evaluation of Christianity compared to the use of religious references by other parties (Schwörer and Romero-Vidal, Reference Schwörer and Romero-Vidal2020).Footnote 4 These parties emphasize the importance of Christianity as part of Western identity, constructing the influx of migrants as a threat to the alleged native culture and mobilizing voters on that ground. By doing so, PRRPs link a “Christian identity” to their political aim of rejecting and degrading outgroup members. At the same time, PRRPs represent themselves as guardians of the religious identity of the native population. In line with the earlier argument of religiosity as a marker for explicating group boundaries, I anticipate that the recourse to Christian values and symbolism, as well as emphasizing Biblical narration in the political communication of PRRPs, might catch on foremost with Christians and, consequently, trigger a stronger response to the messages among them. Moreover, the references to Christianity are likely to affect Christians differently depending on their level of religiousness.

As more salient political messages are more likely to affect public opinion, I argue that the communication of PRRPs has a more substantial impact when these parties have representational strength in the national parliament. Here, a numerically higher representation often accompanies participation in government. Government participation is particularly relevant for PRRPs in power, as they are often still excluded from forming governments due to the cordon sanitaire (Mudde, Reference Mudde2007; but see for Eastern Europe: Minkenberg, Reference Minkenberg2017). The presence of PRRPs in government is not only expected to legitimize their positions, leading to a greater acceptance of radical right-wing views in society, but also the link between their representation and their shaping of public opinion becomes even more relevant. This is because, firstly, PRRPs then receive greater democratic legitimacy due to their high level of political and institutional strength. This should be supported by the fact that PRRPs are currently mostly in coalition with Christian Democratic or conservative parties (Falkenbach, Reference Falkenbach2022). Secondly, PRRPs then receive relatively more attention and visibility in the press and media vis-à-vis the communication of other parties. Both aspects are key to the salience of religious references in their nativist agenda in public discourse. Populist radical right stances are then more likely to be perceived as mainstream positions. This, in turn, is likely to affect the political atmosphere of a country in general, but is particularly likely to affect the nativist sentiments of Christians, who are expected to be more attracted to religious communication by PRRPs than others (i.e. non-religious, other denomination). Due to a higher salience of PRRPs’ messages that politicize Christianity and emphasize the need to defend an alleged Christian heritage against the threat of immigration and foreigners, I hypothesize a stronger tendency toward nativism among religious Christians in countries where a PRRP is in power.

Hypothesis 2 Populist radical right participation in government reinforces the linkage between individual Christian religiosity and nativist attitudes.

Furthermore, PRRPs and their implicit connection to Christian religiosity should matter mainly in those regions in which Christianity is prevalent. However, their actual influence may vary over regions, which is why I am additionally interested in the regional differences within the religiosity–nativism nexus. Therefore, I comparatively explore religiosity’s impact in both European and Latin American contexts and the region’s role in political context’s effect. While successful left-wing populist movements have played a prominent role in most parts of the Latin American continent in the recent past, it is notable that scholars have recently observed the rise of a heterogeneous populist radical right in several of these countries (Althoff, Reference Althoff2019; Díaz et al., Reference Díaz, Rovira Kaltwasser and Zanotti2023; Kestler, Reference Kestler2022; Luna and Rovira Kaltwasser, Reference Luna and Rovira Kaltwasser2021; Tanscheit, Reference Tanscheit2023; Zanotti and Roberts, Reference Zanotti and Roberts2021; Zanotti et al., Reference Zanotti, Rama and Tanscheit2023). There are at least two different arguments regarding the potential moderating effect of the regional context. First, in Latin America, Pentecostal movements are stronger and growing faster than in Europe (Pew Research Center, 2014). This may shape the religious context and lead to a stronger religious effect among Christians on nativism in Latin America.

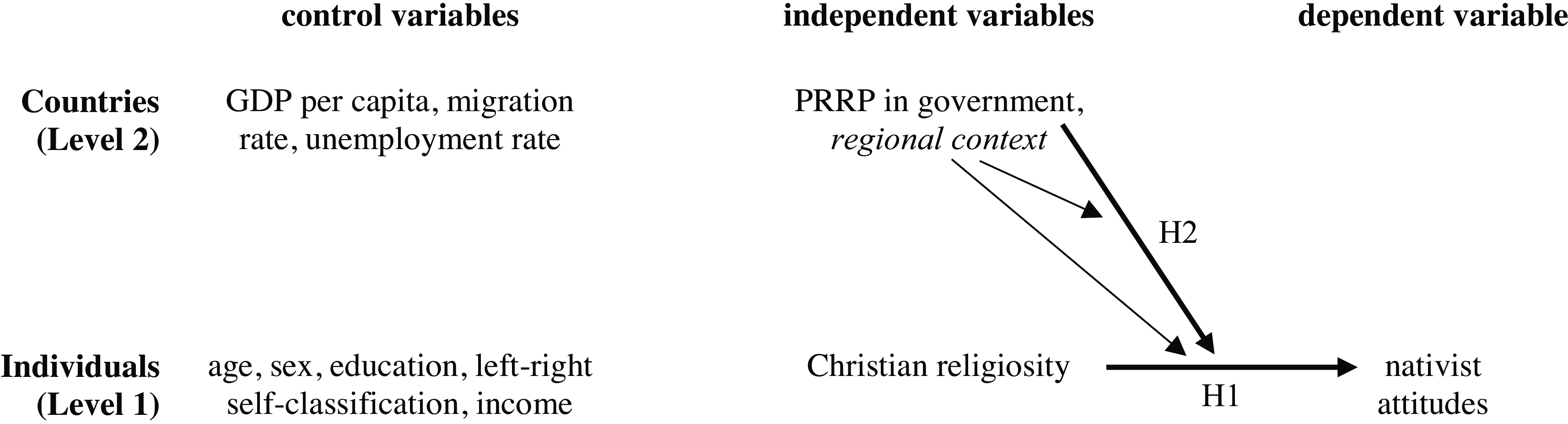

Second, the influx of migrants with a Muslim religious background and the related hostility due to alleged cultural incompatibility is more widespread in Europe (Mudde, Reference Mudde2019; Zaslove, Reference Zaslove2004). Hence, PRRPs in Europe will likely have a stronger target group to blame in their nativist narrative. Furthermore, Christianity-related messages could catch on more easily among Christians if linked to a religious outgroup. Accordingly, this might cause a reinforcing Christian religious impact on nativism in Europe. These contradictory arguments do not lead to a viable hypothesis. Therefore, I take an exploratory approach to the potential moderating effects of the regional context. Figure 1 illustrates the data structure, variables, central hypotheses, and assumptions on the potential regional influence.

Figure 1. Data structure, variables, and assumptions of the analysis.

Research design

In order to address my research question, I employ survey data from the Joint European Values Study/World Values Survey (EVS/WVS, 2022) covering the period from 2017 to 2022. The European Values Study (EVS) and the World Values Survey (WVS) are large-scale survey programs that provide cross-country and cross-sectional data and started cooperating with joint data collection in 2017. The common core of the independently developed questionnaires for both waves EVS 2017 and WVS 7 is defined by joint items. The fourth version of the latest wave includes a large sample with data from 90 countries and provides the necessary items to measure the concepts of interest for testing my hypotheses. Considering the research focus, I restrict my study to countries that belong geographically to the European or Latin American context. Furthermore, countries must either have been categorized by PopuList dataFootnote 5 (Rooduijn et al., Reference Rooduijn, Stijn van Kessel, Pirro, de Lange, Daphne Halikiopoulou, Mudde and Taggart2020) or discussed throughout several articles as related to the rise of the populist radical right in Latin America (Kestler, Reference Kestler2022; Tanscheit, Reference Tanscheit2023; Zanotti and Roberts, Reference Zanotti and Roberts2021). The PopuList data add to the analysis a classification of European parties as populist and far right that have either won at least one seat or at least 2% of the votes in national parliamentary elections since 1989. My final dataset contains 28,026 individualsFootnote 6 nested in 37 countries: 25 from Europe and 12 from Latin America.Footnote 7

Based on the theoretical framework and previous research, I operationalize nativism through stances on immigration. I construct the dependent variable as an index of different dimensions of anti-immigrant attitudes by combining the following five items.Footnote 8 Respective stances are captured by respondents’ evaluation of the impact of immigrants on the development of the respondents’ country, respondents’ trust toward people of another nationality, and concerning jobs scarcity, whether employers should give priority to native people over immigrants. Respondents were also asked whether they could identify people of a different race or immigrants/foreign workers who they would not like to have as neighbors. I reversed the scales so that a higher score indicates a stronger tendency towards nativist attitudes. I standardized the scales, added them to an index, and rescaled them to a 0 to 1 scale to allow for comparability (Cronbach’s alpha 0.6). I also exclude immigrants from the sample.

To operationalize individual religiosity, the key independent variable represents the religious components of the three-dimensional approach of belonging, beliefs, and behavior. In view of my research focus, I exclude respondents without a Christian denomination from the analysis. I measure religious beliefs based on the respondent’s indication of being a religious person, their believe in God, life after death, heaven and hell, and the importance of God in their life. Subsequently, I capture the religious component of behavior based on the frequency of church attendance. I standardized the scales, added them to an index, and rescaled them to a 0 to 1 scale to allow for comparability (Cronbach’s alpha 0.7). My context variable at the country level is binary and represents the presence or absence of PRRPs in government. It indicates whether a country is ruled by a populist radical right party, in which case the variable takes the value 1. A second variable on level 2 considers the regional context of countries included in the sample. I built a dummy variable that states 0 for Latin American countries and 1 for European countries. At the individual level, I control for respondents’ left-right self-classification, education, age, sex, and income. The EVS/WVS dataset (EVS/WVS, 2022) does not provide suitable variables to control for potential attitudinal confounders. From a theoretical perspective, including attitudinal variables as controls would also be challenging, as it implies explaining attitudes with attitudes. However, I perform a robustness check. Finally, I include controls for parameters that could significantly shape the impact at the context level using data from World Bank (2017), i.e., migration rate, GDP per capita, and unemployment rate.

As the central idea of this study is that individuals are affected by the context in which they are nested, I apply multilevel regressions to test my hypotheses. Multilevel models enable the estimation of the influence of individual and contextual characteristics on a dependent variable, which is why such an approach is used specifically for the analysis of hierarchically structured data. With 37 national contexts, the case selection meets the minimum requirement, although there is always an increased risk of influential cases given a small case number (Hox et al., Reference Hox, Moerbeek and van de Schoot2017). I implement several robustness checks to address the challenges of estimating cross-national comparisons in terms of sample selectivity, and the small-N-problem (Schmidt-Catran et al., Reference Schmidt-Catran, Fairbrother and Andreß2019).

The analysis proceeds in four steps. First, a random intercept-only model functions as a null model for entry into multilevel modeling. I implement it to evaluate the model for subsequent regression steps. Second, building on this null model, a random intercept model takes into account the central predictor on level 1, examining the link between Christian religiosity and nativism. This model is based on the assumption that the effect of religiosity is assumed to be constant across contexts. Third, I run cross-level interactions to look at the effects of level 2 predictors on the religiosity–nativism nexus. I analyze whether the participation of PRRPs in government affects the impact of Christian religiosity on nativism as well as whether the regional context has an influence. I then look at a three-way cross-level interaction to test whether the regional context affects the influence of populist radical right participation in government on religiosity’s connection with nativism.

Empirical findings

Given the centrality of Christian religiosity in my research interest, I start with a descriptive overview of its levels among Europe and Latin America based on the Joint EVS/WVS data (EVS/WVS 2022). As for the distribution in the sample, an overall mean of 0.63 (sd = 0.23) is given for religiousness. Country mean scores vary from 0.41 in Sweden to 0.76 in Guatemala. I also find slight differences between Europe (mean = 0.58) and the Latin American region (mean = 0.72). Furthermore, across the 37 countries, the share of Christians who tend to be highly religious, as indicated by scores above the midpoint of the religiosity scale, is, on average, about 71%. I find the proportion of religious Christians in the countries under study non-negligible, which indicates that this group may affect nativism. Nativism among Christians varies similarly. With a mean of 0.21, the lowest level is recorded in Sweden, while the highest level is found in Hungary. Hungary’s country score of 0.58 is thereby clearly higher than the overall nativism mean of 0.40 (sd = 0.19). Government participation of PRRPs scores a mean of 0.2 (sd = 0.4) across the sample. In eight out of 37 countries, PRRPs are in office. Thus, the data still provide sufficient variance between contexts to test my hypotheses. However, the distribution of PRRPs in government over the two regions is rather unbalanced. Whereas PRRPs participate in government in seven European countries, this is only the case for Brazil in the Latin American context (Table A1 in the appendix).

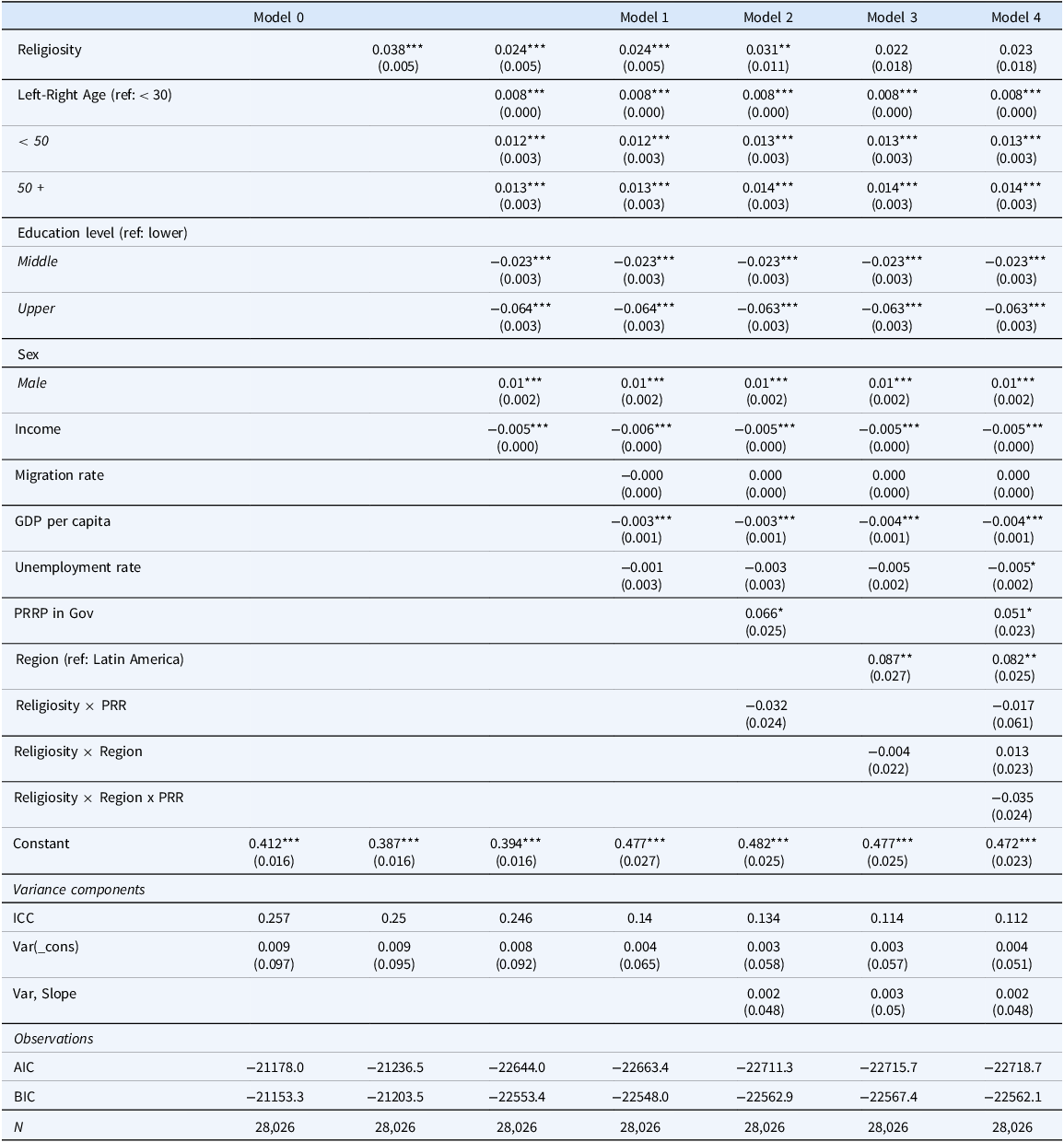

As an adequate test of the relationship, I use multilevel regression to model how the individual religiosity of Christians affects their nativist attitudes. The multilevel analysis operates with individuals (at level 1) nested in European and Latin American countries (at level 2) and is based on the stepwise approach previously described. The full results can be found in Table 1. The intraclass correlation (ICC), calculated based on empty model 0, is 0.257 at the country level. Thus, 26% of the total variance of individual nativism is, thus, explained by differences between context units.

Table 1. Results from multilevel regression models on nativism among Christians

Source: Joint EVS/WVS 2017–22 (EVS/WVS 2022).

Note: Regression coefficients (with standard errors) from multilevel models with individuals nested in countries. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Model 1 stepwise introduces independent variables at both levels, the individual and the contextual one. First, I add religiosity as a level 1 predictor. Second, at the individual level, I control for sociodemographic and socioeconomic influences and ideological positioning on the political spectrum. Third, at the contextual level, I include migration rate, GDP per capita, and unemployment rate as potential explanatory factors for an increased tendency toward nativism in society. The effect of religiosity among Christians is found to be weakly positive and remains robust across the steps in model 1. Taken together, my findings support the first hypothesis. This implies that the more religious Christians are, the more likely they are to hold nativist attitudes.Footnote 9 It is argued and demonstrated in the literature that denominational differences are relevant when analyzing political attitudes and behavior of individuals (Falter, Reference Falter, Ruff and Großbölting2022). From an institutional perspective, for example, Catholicism has a transnational character (Kaiser, Reference Kaiser2007), in contrast to the strongly nationally oriented Protestant church structures (Kalyvas and van Kersbergen, Reference Kalyvas and van Kersbergen2010). On the other hand, the argument of successive liberalization often refers to the Protestant churches in (Western) European countries (Cremer, Reference Cremer2021; Reference Cremer2023). To reflect the heterogeneity within the group of Christians, I include separate checks for the Catholic and Protestant denominations in my sample. While religiosity is correlated with nativism among Catholics (N = 15,228), there is no statistically significant effect on nativism for Protestant respondents (N = 9,144) when controls are included. Looking at Orthodox Christians (N = 2,339) reveals a substantially stronger association of religiosity with nativism (see Tables B2–B4 in the appendix). With regard to the disconnected nature of religious components and the discrepancies in religiosity’s link to nativism reported in previous work, additional checks partially support the findings of Immerzeel et al. (Reference Immerzeel, Jaspers and Lubbers2013) on the impact of religious beliefs. Both self-reported belief in God and belief in heaven are substantially correlated with nativism. In conclusion, beliefs appear to be the primary factor driving this association, while belonging and behavior contribute only marginally – with behavior (i.e., church attendance) showing a negative tendency (Table B5 in the appendix).

As stated in the second hypothesis, I expect populist radical right government participation to reinforce the effect of religiosity on nativism among Christians. For this, I add their presence or absence in government as the key explanatory variable at the country level. A statistically significant effect emerges when controlling for GDP per capita. Taking into account the economic situation, there is a slight supportive effect of governing PRRPs on nativist attitudes in society. However, the interaction between religiosity and their presence, as estimated in model 2, does not provide any indication of an impact on nativism. In line with these observations, hypothesis 2 finds no evidence.

Models 3 and 4 integrate the regional context at the country level for my exploratory comparison of Christian religious influence on nativism. First, a statistically significant positive regional effect shows up when controlling for GDP per capita. Considering GDP per capita in model 3, a relatively stronger tendency toward nativist attitudes can be observed in Europe (Latin America as reference category). Second, given the absence of statistical significance, I find no support for the cross-level interaction between religiosity and region. This is consistent with the previously reported effect of religiosity itself, which no longer exists. Thus, one could suggest that in Latin America, there is no effect, or at least only a weak effect, of religiosity on nativism. Indeed, a model estimated separately by the region shows no effect of religiosity for Latin America (Table B6 in the appendix). Model 4 runs the theoretical consideration of a three-way cross-level interaction to test whether the regional context affects the impact of populist radical right participation in government on religiosity’s relation to nativism. However, I do not find a significant effect. Weak positive effects of government participation and the region on nativism occur when controlling for the economic situation. However, due to the time period studied, only one national context with a populist radical right party in power remains for analysis in Latin America.

In sum, a higher level of Christian religiosity across the 37 countries in Europe and Latin America is associated with nativist attitudes. This finding supports previous work on the European context by Montgomery and Winter (Reference Montgomery and Winter2015) and, in part, Immerzeel et al. (Reference Immerzeel, Jaspers and Lubbers2013). Since there is no indication for the presence of PRRPs in interaction with religiosity to affect nativist attitudes, some further considerations are required. First, due to the cordon sanitaire that still exists in several countries, it seems worthwhile to consider the representative strength of PRRPs in their national parliaments, even if they are not (yet) in government. Second, especially in the case of Latin America, it should be remarked that the populist radical right is only beginning to emerge and, due to political and institutional factors such as the presidential system, must secure strong voter support to gain access to government. However, the results do not provide further clarification when I take into account the vote shares of PRRPs in the last national election instead of the dichotomous presence or absence in government (Table C1 in the appendix).

The findings demonstrate that government participation by PRRPs may indeed reinforce a nativist tendency in general. However, there is no evidence that the levels of nativism among religious Christians are influenced by their presence. Such an observation deserves a broader discussion on why this political context might be less determinant. The national level of secularization needs to be considered. In a highly secularized society, religion should no longer be so deeply rooted in the national culture and therefore less easy to use. Thus, the contrast regarding the level of nativism among Christians presented above between Sweden and Hungary seems to indicate the importance of religion in national culture rather than government participation in a PRRP. This means that the lack of a PRRP in government in Sweden during the period under study should be less of a reason for a lack of influence. The religious landscape also includes the national churches as institutionalized form of religion. In addition to structural factors, particularly with regard to the church-state relationship, their status and their substantive positioning in the public discourse are relevant as guidance for their respective faith communities (Cremer, Reference Cremer2023). Germany, for example, illustrates the increasing liberalization of major Christian churches in Western Europe over recent decades, particularly through their advocacy for refugees, as reflected in the 2016 statement of the German Bishops’ Conference and the Protestant Church’s commitment to sea rescue initiatives. This could mean that PRRPs have less influence on the religious committed Christians. In Germany, the churches have become an important critical voice against right-wing narratives and mobilization in public discourse (Cremer, Reference Cremer2023). Their clear opposition to the Alternative for Germany (AfD) is said to have created a “social firewall” among Christian-religious adherents (Cremer, Reference Cremer2021).

Regarding the political context of the countries under study, it is important to reflect on the ways in which PRRPs politicize religion and the intensity with which they do so. While some of these parties distance themselves from religion of any kind, others are in turn closely associated with religiosity. First of all, Law and Justice (PiS) in Poland; but also Fidesz in Hungary, for whose support religiosity can be identified as a central factor (Marcinkiewicz and Dassonneville, Reference Marcinkiewicz and Dassonneville2022). However, the literature also mentions above-average support from nominal fundamentalist Catholics for the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ), which is known for its anti-clerical roots (Arzheimer and Carter, Reference Arzheimer and Carter2009; Minkenberg, Reference Minkenberg and Rydgren2018). Previous studies also already point to the relevance of certain other party families present in a country’s political system (Marcinkiewicz and Dassonneville, Reference Marcinkiewicz and Dassonneville2022; Stankov and Živković, Reference Stankov and Živković2022). These factors play into the context. This is why we may not get a clear picture of the impact from a broad comparative perspective.

Furthermore, the finding might lead back to the widely discussed ambivalence of religiosity. In light of its aforementioned unifying character, it is quite arguable that there are religious Christians who are not taken in by populist radical right stances. On the contrary, they cherish Christian ethics such as compassion and love thy neighbors. Insights on institutional legitimization’s impact of radical right parties on ideological polarization shed further light on this occurrence. Arguing for both legitimization and a backlash effect, Bischof and Wagner (Reference Bischof and Wagner2019) find that PRRPs’ entrance into parliament pushes voters further to the fringes on both sides of the political spectrum in response to salient radical messages. Thus, while religious connotations in the rhetoric of PRRPs might appeal strongly to Christians and reinforce their nativist sentiments on the one hand, such references might also be rejected and provoke a backlash on the other. Such opposing effects are important to consider when interpreting the impact of PRRPs in power on nativism among Christians.

I performed a number of additional checks to further explore my results and probe their robustness; all of these tests are reported in the Appendix C. To control for attitudinal confounders that could plausibly correlate with both religiosity and nativism, I ran the main model with proxy items for the control variables. The outcome confirms the robustness of the observed effect of religiosity on nativism (Table C5 in the appendix).

Conclusion

In this study, I aimed to examine the relationship between Christian religiosity and nativism and to investigate a moderating effect of PRRPs in power on this linkage. The research question sought to determine the influence of populist radical right participation in government on the impact of individual religiosity on nativism. First, I argued that Christian religiosity positively influences nativist attitudes and, second, that this effect should be reinforced by populist radical right participation in government. In short, I stated that if populist radical right messages gain salience for public discourse – by PRRPs taking office – broadly expressed anti-immigration stances and the politicization of Christianity should further strengthen religiosity’s influence on nativism. Findings of my analysis partially confirm these expectations. The first hypothesis finds evidence in results showing an association between Christian religiosity and nativism. In line with my theoretical assumption, stronger religiosity among Christians is related to a higher tendency toward nativist attitudes. Therefore, this study supports the conclusion that the more religious Christians are, the more they tend to hold nativist attitudes. This stresses the notion that Christian religiosity might matter in shaping attitudes toward nativism. It is noteworthy that this association seems to be primarily driven by beliefs while belonging and behavior play a minor role. These findings are consistent with previous research that highlights the divergent relevance and direction of different religious components, in particular studies emphasizing the reinforcing role of beliefs. Regarding the second hypothesis, findings do not confirm the idea that PRRPs in government reinforce Christian religiosity’s impact on nativism.

The implications of these findings are noteworthy. From an academic standpoint, this research contributes to the existing literature by underlining the strengthening link between Christian religiosity and nativism. Furthermore, it contributes to understanding how religiosity can be interwoven with attitudes that clearly question the plurality of societies.

Considering the reported religiosity–nativism association, the assumption of a PRRPs’ impact indeed seems plausible, so the lack of evidence when accounting for PRRPs participation in government might suggest that the context-related examination has to be more differentiated. Perhaps more insightful than PRRPs’ presence in government might be their communication to mobilize voters. Another suggestion is that it is not attitudes that are becoming more nativist, but rather that PRRPs in office might polarize these highly religious Christians by building their nativist discourse on the construction of a threat to the “Christian West” that must be defended. In this way, an increase in Christians’ ingroup attachment and outgroup hostility, rather than their actual stronger nativist tendencies, would challenge a plural society.

Thirdly, given the evidence of an association between religiousness in general and nativism, the explicit statement on Christian religiosity can be questioned. Finally, I highlight some limiting aspects of this study. Firstly, operationalizing the dependent variable remains a challenge. The dependent variable is constructed as an index combining five items representing different dimensions of nativist attitudes, as mentioned above. Potentially, these items are measured by scales that are too different to adequately capture the concept of nativism. Secondly, the analysis lacks measurements over different time periods and over time, leading to two main shortcomings. The first is that Brazil is thus taken as the only case with PRRPs in government for the entire Latin American region; the second is that differences in the influence of governments on the religiosity–nativism nexus within a country context cannot be compared.

Thus, subsequent research should examine the linkage for other denominations as well as account for different Christian denominations using an appropriate sample. Future research needs to overcome these limitations using data that provides a more straightforward construction of nativism. It may also be fruitful to consider a broader time period. Looking at multiple terms of office allows studying PRRPs’ impact in a greater number of countries, while the examination over time provides the opportunity to identify possible trends or notable changes within a country context. Furthermore, I raise the importance of distinguishing between populist and RRP parties in further analyses. In addition, the question of whether it is Christian religiosity or religiosity of all kinds needs to be analyzed in the future.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048325000045

Financial support

The study was conducted during the author’s fellowship at the Cluster of Excellence Religion and Politics, University of Münster, Germany.

Competing interests

The author declares none.

Lucienne Engelhardt is a PhD Candidate at the Cluster of Excellence Religion and Politics, University of Münster, Germany. Her research examines the interplay between religion and right-wing populism in attitudes and discourse, using survey data and computational text-as-data approaches.