In two cases in the 1990s, the Supreme Court addressed whether police could conduct suspicionless searches under the Fourth Amendment. In each instance, officers approached men who were unable to avoid the searches. The first, Joell Palmer, was driving in Indianapolis when police stopped him at a traffic checkpoint. The second, Terrance Bostick, was a passenger on a Greyhound bus in Fort Lauderdale when police boarded. The purpose of both searches was to detect criminal wrongdoing, although police had no reason to suspect either man of criminal activity. In Indianapolis, the police surrounded Joell’s stopped car, conducted visual searches, and dogs smelled for narcotics. In Florida, police similarly restricted Terrance’s freedom of movement on the bus and searched his belongings. Both men appealed their cases to the U.S. Supreme Court alleging police misconduct, and Justice Sandra Day O’Connor wrote the majority opinion in each. Joell prevailed, but Terrance did not. With such similar facts and legal issues, what explains the different outcomes?

One possible explanation is the men’s underlying criminality. Drug interdiction efforts guided police officers’ activity in both Indiana and Florida. Indianapolis police found no evidence of narcotics, and Joell’s lawyers stressed his innocence. However, in Florida, police singled out Terrance among all the bus passengers, found drugs in his luggage, then arrested and convicted him of drug trafficking. Although the question of guilt or innocence is left to trial courts, Joell’s innocence may have influenced Justice O’Connor. Noting that the Court allows police to conduct stops in many circumstances, O’Connor carved out an exception to protect law-abiding citizens like Joell.Footnote 1 In Terrance’s case, O’Connor ruled quite differently.Footnote 2 Despite similar circumstances, O’Connor determined that Terrance had a choice in cooperating and could have left, even though he was seated and the police—displaying badges and weapons—blocked his path. Perhaps the fact that Terrance was ultimately convicted of a crime influenced O’Connor.

Another explanation for the different outcomes is Joell and Terrance’s racial/ethnic background. Joell was a white man driving a car, while Terrance was a Black man on a bus.Footnote 3 Racial identity provides cues to the public—including political elites—about an individual’s supposed criminality. Black Americans are consistently viewed as more criminal than white Americans, affecting individuals’ perceptions and actions (Eberhardt Reference Eberhardt2020). O’Connor’s worries about inconveniencing motorists like Joell may be because white men are viewed as less criminal, less angry, and less capable of violence (Eberhardt Reference Eberhardt2020), thus making them more deserving of positive government treatment. When confronted with a Black man, O’Connor shows no sympathy. In her opinion, O’Connor is untroubled by Terrance’s emotional state during the encounter and suggests he could freely leave the bus despite evidence to the contrary. O’Connor’s lack of empathy for Terrance may be due to stereotypes linking Black men with criminality. Thus, racial bias may have swayed the Court’s decision.

These cases, and others like them, drive our research. We ask how racial bias—conscious or not—influences justices’ votes and whether this affects the language in their opinions. Viewed with an understanding of how race and racism affect American politics, O’Connor’s sympathetic portrait of Joell, a white man, but indifferent portrayal of Terrance, a Black man, is unsurprising. Racism is a common feature of American society, often emerging through subtle and unconscious beliefs about racial groups’ status (Lawrence Reference Lawrence1987). Through this lens, these cases are not simply impartial applications of the law, nor are they easily understood by traditional extralegal factors. They are best interpreted as broader beliefs about which races, ethnicities, and genders deserve positive treatment, and which do not, based on stereotypes law has created about different groups’ worth.

We argue that Supreme Court justices, through their votes and written opinions, reinforce America’s stereotypes that cast nonwhite individuals as criminals and whites as innocent. This is important because scholarship on the Court frequently neglects the role of race. As O’Connor’s opinions illustrate, ostensibly neutral language often masks racial biases. Butler (Reference Butler2010, 246) contends that by “rarely mention[ing] race,” the Court is invested in “[expanding] the power of the police against people of color.” To understand how race and racism affect modern Court decisions, we must look beyond explicit discrimination and consider the subtle mechanisms by which racial biases are perpetuated.

We examine bias’s role in the Court’s opinions by investigating how the Court invokes race and how justices use crime as a shorthand for racial identity. Analyzing litigants’ race and underlying criminal offense, we ask whether U.S. Supreme Court justices treat criminal defendants differently based on racialized stereotypes about criminality. We argue justices uphold stereotypes that nonwhite Americans are more criminal and more likely to commit violent crimes, leading justices to vote in favor of white, nonviolent litigants. We find extralegal factors like political ideology condition justices’ reactions to such stereotypes, as conservative and liberal justices treat criminal defendants differently. Building on previous work applying text analysis to U.S. court opinions and finding implicit racial biases (Rice et al. Reference Rice, Rhodes and Nteta2019), we supplement our statistical analyses and examine several instances where the Court uses racialized criminal stereotypes in its opinions. Much like Joell and Terrance’s cases, justices’ biases reveal themselves in the narrative of the facts and law. Our results offer evidence the Court constructs what it means to be criminal and nonwhite.

Bias at the Court

In his pioneering empirical study of Supreme Court justices’ votes, Herman Pritchett (Reference Pritchett1941, 890) observed that “no one doubts that many judicial determinations are made on some basis other than the application of settled rules to the facts or that justices of the United States Supreme Court … are influenced by biases.” Subsequent research has consistently confirmed that justices’ personal preferences shape their decisionmaking.

Although scholars often conceptualize these preferences along a conservative-liberal continuum, a growing body of literature underscores the importance of life experiences (Harris and Sen Reference Harris and Sen2019). Yet because the Supreme Court has been—and remains—an overwhelmingly white institution, justices’ life experiences have been remarkably uniform. Indeed, only four justices of color have served in the Court’s history, with three of those currently on the bench. The lack of racial diversity has significant implications for the Court’s decisions. When justices deliberate, their “private attitudes” influence their colleagues and affect case outcomes (Kastellec Reference Kastellec2013, Pritchett Reference Pritchett1941), suggesting that bias—rooted in a narrow range of lived experiences—is woven into the very fabric of the institution.

Likely because of this, the Court has a long history of burdening nonwhites. Across a range of cases, including immigration, anti-miscegenation, and segregation, the Court created racial differences that benefit whites. For example, in naturalization cases, the Court determined only whites were eligible for full citizenship rights, denying these privileges to anyone deemed nonwhite (Haney-Lopez Reference Haney-Lopez1997). Even after overturning many of these decisions, racial group constructions endure, with new forms and justifications. Bias still plays a role in the Court’s decisions, with justices reinforcing racialized stereotypes about criminality that it helped create.

Historical judicial precedent was overt in its racial stereotyping, but today’s Court displays subtler forms of racism, masking bias in race-neutral language (Lawrence Reference Lawrence1987). This is a hidden version of racism since individuals rationalize choices with color-blind language and justify racial inequalities through stereotypes about who deserves lenience and punishment (Kang et al. Reference Kang, Bennett, Carbado, Casey and Levinson2012; Quintanilla Reference Quintanilla2013). Form aside, the unequal judicial outcomes are the same.

Modern color-blind racism is particularly prominent as it is often unconscious (Kang et al. Reference Kang, Bennett, Carbado, Casey and Levinson2012). Even racially liberal justices may unintentionally favor white litigants over their nonwhite counterparts or make judgments based on unfounded stereotypes (Rachlinski et al. Reference Rachlinski, Lynn Johnson, Wistrich and Guthrie2008). In interviews with judges conducted by Clair and Winter (Reference Clair and Winter2016, 340), judges admitted racial discrimination “permeates the entire [judicial] system.”

Scholars have also found the judicial branch upholds societal stereotypes about litigants’ race and gender. For example, female defendants—who society constructs as weaker and more virtuous than men—are convicted less frequently (Doerner and Demuth Reference Doerner and Demuth2014) and sentenced more leniently (Freiburger and Hilinski Reference Freiburger and Hilinski2013). Similarly, the judicial branch reinforces racial stereotypes characterizing Black Americans as more violent, more likely to abuse drugs, and more crime-prone than other groups by punishing Black men and women more harshly than other racial groups (Moore and Padavic Reference Moore and Padavic2010). Ideology conditions these effects. Cohen and Yang (Reference Cohen and Yang2019) find that compared to their Democratic counterparts, Republican-appointed judges sentence Black defendants to three more months than non-Black litigants.

Biases may be especially likely to appear in court decisions. Bias is more common where political elites have ample discretion (Kang et al. Reference Kang, Bennett, Carbado, Casey and Levinson2012), situations are subjective, and outcomes can be justified in non-racialized terms (Quintanilla Reference Quintanilla2013). These characteristics perfectly fit courts, particularly the highest court. Although bound by precedent, judges have a range of cases from which to choose (Matthews Reference Matthews2024) and discretion to choose which precedent they address and ignore (Hinkle Reference Hinkle2015). Justices rationalize decisions using factors beyond stare decisis, including personal relationships (Hazelton, Hinkle, and Nelson Reference Hazelton, Hinkle and Nelson2023), and shared professional backgrounds and identities (Choi and Gulati Reference Choi and Mitu Gulati2008; Matthews and Hinkle Reference Matthews and Hinkle2025). Racial group biases also influence justices’ decisions, particularly when justices need to “fill in the blanks” about case specifics by relying on group stereotypes (Gill et al. Reference Gill, Kagan and Marouf2019, 513). Because the Court has wide discretion and justices are not immune to bias, it is likely the Court will enforce racial stereotypes about crime.

Identifying all the ways bias can enter Supreme Court decisions can be challenging. One potential contributor is attorneys’ legal briefs and oral arguments (Johnson, Wahlbeck, and Spriggs Reference Johnson, Wahlbeck and Spriggs2006). By strategically framing legal issues, attorneys shape how cases are understood. Justices often borrow language directly from attorneys’ briefs (Corley Reference Corley2008). Using plagiarism-detection software, Corley finds the Court is more likely to incorporate briefs’ text when the arguments are of high quality, there is ideological compatibility between the briefs and the justices, and the case is not politically salient.

Still, two considerations caution against attributing justices’ bias solely to attorneys’ briefs. First, many criminal procedure cases are both politically and legally salient, making it less likely that the justices will adopt a high percentage of attorneys’ language. Second, even when the Court does borrow text, the justices ultimately decide which words and arguments appear in the final opinion. Thus, while copying and pasting from briefs can amplify existing bias by lending the borrowed language the Court’s imprimatur, the justices remain responsible for endorsing or rejecting those narratives.

Racialized Stereotypes about Criminality

In both its laws and enforcement, the American criminal justice system upholds a white racial hierarchy, portraying people of color, especially Black Americans, as criminals. For example, to combat growing racial equality during the Reconstruction Era, whites in the Jim Crow South used criminal justice policies to keep Black Americans politically and economically disenfranchised (Alexander Reference Alexander2020). Policymakers use the legal system to target Black Americans by linking drug use with Blackness and intensifying the punishment for even minor offenses. This produces a system where one in five Black men are likely to face incarceration in their lifetime (Robey et al. Reference Robey, Massoglia and Light2023). Despite the legal system’s attempts to claim race-neutrality, these policies construct Black Americans as “criminal” and “dangerous” (Goff et al. Reference Goff, Eberhardt, Williams and Christian Jackson2008). Crimes are racialized, and race is criminalized, meaning the relationship is endogenous: when Americans think of crime, they think of Black Americans, and when they think of Black Americans, they think of crime (Eberhardt et al. Reference Eberhardt, Atiba Goff, Purdie and Davies2004). This stereotype is so strong that driving while Black or Brown itself becomes a criminal act (Butler Reference Butler2010).

These arguments extend beyond Black Americans. The legal system disproportionately hurts other nonwhite groups, such as Latinos. For over sixty years, immigration enforcement has been aimed at curbing unauthorized immigration from Latin America (Maltby et al. Reference Maltby, Rocha, Jones and Vannette2020). In 2020, 95.4% of immigrants deported were from Latin American countries (U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement 2020) despite making up only 76% of those unauthorized (Ward and Batalova Reference Ward and Batalova2023). The language and enforcement of these laws paint Latino immigrants and, more broadly, all Latinos, as “grave [threats] to the nation” (Massey and Pren Reference Massey and Pren2012, 5). As with Black Americans, laws and agencies reinforce views that Latinos are criminal.

The legal system also stereotypes whites who, unlike people of color, benefit from these stereotypes. Maltby (Reference Maltby2017) argues when criminal justice laws socially construct nonwhites as criminal, whites are implicitly categorized as the opposite. With each law stereotyping Black Americans as criminals or Latino Americans as undocumented, whites are portrayed as law-abiding, native-born, and morally upstanding. Society assumes white Americans do not commit crime. Given that Supreme Court justices are not immune to societal biases, we expect justices will be more likely to vote in favor of white litigants.

H1: Supreme Court justices will be more likely to vote for white litigants than nonwhite litigants.

Racialized Stereotypes about Specific Offenses

Many crimes are stereotyped as belonging to specific racial groups, with more severe crimes framed as nonwhite and punished more harshly. For instance, some crimes are viewed as stereotypically “Black,” including violent crimes (Hurwitz and Peffley Reference Hurwitz and Peffley1997, 380), “blue-collar crimes” like assault or car theft (Gordon, Michels, and Nelson Reference Gordon, Michels and Nelson1996), and drug crimes (Beckett et al. Reference Beckett, Nyrop, Pfingst and Bowen2005). Sentences for violent and drug crimes are especially harsh, likely because these are viewed as “Black.” The sentencing disparity between crack-cocaine and powder cocaine highlights this. Because the former is stereotypically Black and the latter is stereotypically white, crack-cocaine receives significantly harsher sentences than powder-cocaine. Even President Obama’s attempt to bring equity to this policy left possession of the “Black drug” with longer sentences than the “white drug.”

Nonviolent crimes, like embezzlement or tax fraud, are stereotyped as “white” (Sunnafrank and Fontes Reference Sunnafrank and Fontes1983). White-collar offenders rarely receive real punishment, as the lack of jail time for Wall Street executives after the 2008 financial crisis highlighted (Eisinger Reference Eisinger2014). Offense-based stereotypes go beyond Black and white; offense type affects whether an individual is perceived to be white, Black, Native American, or Asian (Saperstein et al. Reference Saperstein, Penner and Kizer2013), and local immigration policing leads to greater arrests of native-born Latinos as unauthorized immigrants are presumed to be Latino (Coon Reference Coon2017).

We expect Supreme Court justices will reproduce racial bias even when a litigant’s race is unknown. Because criminal offenses are racialized, justices will be more likely to vote in favor of litigants convicted of “white” crimes while voting against those with violent offenses that have been stereotypically linked with people of color.

H2: Supreme Court justices will be more likely to vote in favor of litigants whose offenses are nonviolent, including white-collar crime, compared to litigants with more violent offenses.

Stereotype Adherence and Justice Political Ideology

The Supreme Court plays a crucial role in maintaining racial ideology, but racial bias is not the only factor affecting judicial decisionmaking. Justices’ political ideology matters, yet in the American context, it is difficult to disentangle ideology from racial attitudes (Westwood and Peterson Reference Westwood and Peterson2020). Partisan elites use coded language that reinforces stereotypes depicting Black Americans as criminal to demonstrate they are “tough on crime” (Alexander Reference Alexander2020). Recent policy shifts among liberal-leaning elected officials, however, suggest that criminalized racial stereotypes may exert less sway on certain decisionmakers. Some Democrats, for example, have advocated for police reform and shown greater leniency towards immigrants (Linskey Reference Linskey2020; Bernal Reference Bernal2023), raising the possibility that liberal justices may similarly vote in favor of nonwhite litigants, conferring both symbolic and real benefits. Supporting this possibility, existing research shows that Republican-appointed judges impose longer sentences than their Democratic-appointed colleagues for identical offenses (Schanzenbach and Tiller Reference Schanzenbach and Tiller2008).

More broadly, ideology affects how justices respond to racial and criminal stereotypes. The mere presence of nonwhites or violent offenders can “activate” individuals’ latent biases (Peffley and Hurwitz Reference Peffley and Hurwitz2007), influencing how justices interpret case information. Political parties differ in their beliefs about the crime and justice: Republicans attribute social problems, such as crime and mass shootings, to individual failings, whereas Democrats view such issues as symptomatic of structural deficiencies (Joslyn and Haider-Markel Reference Joslyn and Haider-Markel2013). One such external flaw is the role racial discrimination plays in the justice system—an argument Democrats and Independents are more likely to accept than Republicans (Peffley and Hurwitz Reference Peffley and Hurwitz2007). Consequently, Democrats may attribute the disproportionate incarceration of Black men to systemic causes such as poverty and police bias, offering more sympathy to offenders (Unnever Reference Unnever2008). When liberal-leaning justices evaluate cases involving Black defendants, they may be more inclined to reject criminal stereotypes, developing counter-narratives that align with their ideological perspectives. In contrast, conservative-leaning justices are more likely to accept and reinforce prevailing racialized constructions of crime, shaping their decisions accordingly.

Justice ideology may be important for another reason. Supreme Court justices are not neutral observers of the law. Their personal identity plays a role in how they experience institutions and reach decisions. Liberal justices on the current Court are more likely to be women, nonwhite, and to belong to nondominant religions (e.g. Judaism). Despite their elite status, these more marginalized aspects of their identities may lead them to view cases differently than their white male counterparts.

Based on ideology’s strong and consistent effect, and its interplay with stereotypes, we expect judges will treat litigants differently depending on the litigant’s race and the crime they committed. This leads to our third hypothesis:

H3: Conservative justices will be more likely to vote against nonwhite and violent offenders than their liberal counterparts.

Data and Methods

To test our hypotheses about bias’s role in the Court, we use criminal procedure cases from the Supreme Court Database for the 2005–2017 terms (Spaeth et al. Reference Spaeth, Epstein, Martin, Segal, Ruger and Benesh2020). The Court heard 291 criminal procedure cases during this period. We chose criminal procedure cases for several reasons. First, it’s a salient policy area for the public, and the Court decides several criminal procedure cases each term, as the sheer number of cases during the 13 terms illustrates. Second, researchers have previously applied theories of racialized stereotypes to criminal justice policies (see, e.g. Maltby Reference Maltby2017), allowing us to compare how legislators and justices treat groups.

We collected several pieces of information for all cases. For the named parties in the case, we identified the state official and the party challenging the state. For example, in Dunn v. Madison, a death penalty case, the petitioner Jefferson Dunn, was the Alabama Department of Corrections commissioner. The respondent, Vernon Madison, was challenging his death sentence. For our purposes, Dunn represents the state and Madison is the litigant. We focus on the individual whose case is against the State (either a federal or state government entity), who we refer to as litigant or defendant.

We coded the litigant’s racial identity, gender, and nature of the underlying crime. To do so, we relied on news articles and court documents. From these sources, we could identify the race of 152 litigants. When race was unavailable from these sources, we relied on a website of Census records to determine the probability of the defendant’s race based on their last name, since last names may suggest race.Footnote 4 Experimental studies find names serve as “subtle psychological cues” about one’s race (DeSante Reference DeSante2013, 347). At the Supreme Court, the justices may pick up racial cues based on the litigants’ name alone, although it’s likely other clues signal litigants’ racial identity.

Because we cannot rely on last name alone to identify race with total certainty, we set a minimum threshold of 75% likelihood that Census records correctly identified a litigant’s race, meaning that 75% or more of the individuals in the US with that last name belong to one race. This allowed us to racially identify an additional 60 litigants.Footnote 5 Our final sample includes 111 white, 64 Black, and 37 Latino litigants.Footnote 6 Cases where race could not be confidently identified were dropped.

We coded gender using court documents and news articles and by relying on the individual’s first name. The vast majority (95.9%) of defendants appearing before the Court in our sample are male. Eleven defendants identified as cis- or transwomen.

We expect the defendant’s original crime will affect justices’ decisions. Relying on the same sources as gender and race, we collected and coded the original crime. We then narrowed these to four categories: murder, other violent crime, nonviolent crime, and white-collar crime. Several cases included more than one of these issues. For instance, some individuals who were originally charged with murder also committed robbery or another violent crime. In these instances, we coded the crime as the most serious offense. Murder offenses made up 36% of the cases. Other violent crimes included sexual offenses, kidnapping, and crimes using the phrases “assault,” “battery,” or “violence” and were nearly 17% of the cases. Nonviolent offenses accounted for roughly 34% of cases. This included burglary, illegal weapons possession, alcohol and drug abuses, and immigration. White-collar crimes, which made up around 9% of cases, included financial crimes, conspiracy, and fraud. In 15 cases, litigants were the injured party (i.e. the state did not charge them with a crime). We dropped these cases.Footnote 7

We hypothesize the effect of litigant race and crime will affect the likelihood justices vote in favor of the citizen. However, based on past scholarship, we suspect the effect of a citizens’ race and original offense on outcomes depends on a justice’s ideology. To measure this, we rely on Martin-Quinn (Reference Martin and Quinn2002) scores. To address potential endogeneity, we lag justices’ ideology scores. However, the results remain unchanged when non-lagged ideology is used. For the period we examine, the mean Martin-Quinn score is 0.11, indicating an ideologically moderate justice. The scores range from -3.48, with Sotomayor being the most liberal justice, to 3.96, with Thomas being the most conservative. To test whether the effect of a litigant’s race and original crime on outcomes varies by justice ideology, we run a series of interaction models: one for justice ideology interacted with litigant race, and one for justice ideology interacted with target crime. Finally, to see if all three factors matter jointly, we run split-sample models based on litigant race.

The dependent variable is each justice’s vote for the litigant. We designed the analytic approach to estimate the predictors of support for litigant groups, as well as to explore the ways this varies across justices. Because the justices do not sit on the Court at the same time, we needed to be careful combining the data. We chose to “pool” the data by justice-case. This means we isolated each of the 13 justices who served on the Court during the period and created a universal variable, “justice vote,” measuring 1 when the justice voted in favor of one of the litigant groups and zero otherwise. We test our hypotheses using multilevel logit models with a random intercept that varies by case.Footnote 8 We also control for the legal issue, whether the case involved the death penalty, whether the State is the petitioner, as well as the gender and race of the justice. Finally, we include the term in which the Court decided the case.Footnote 9

Quantitative Analysis

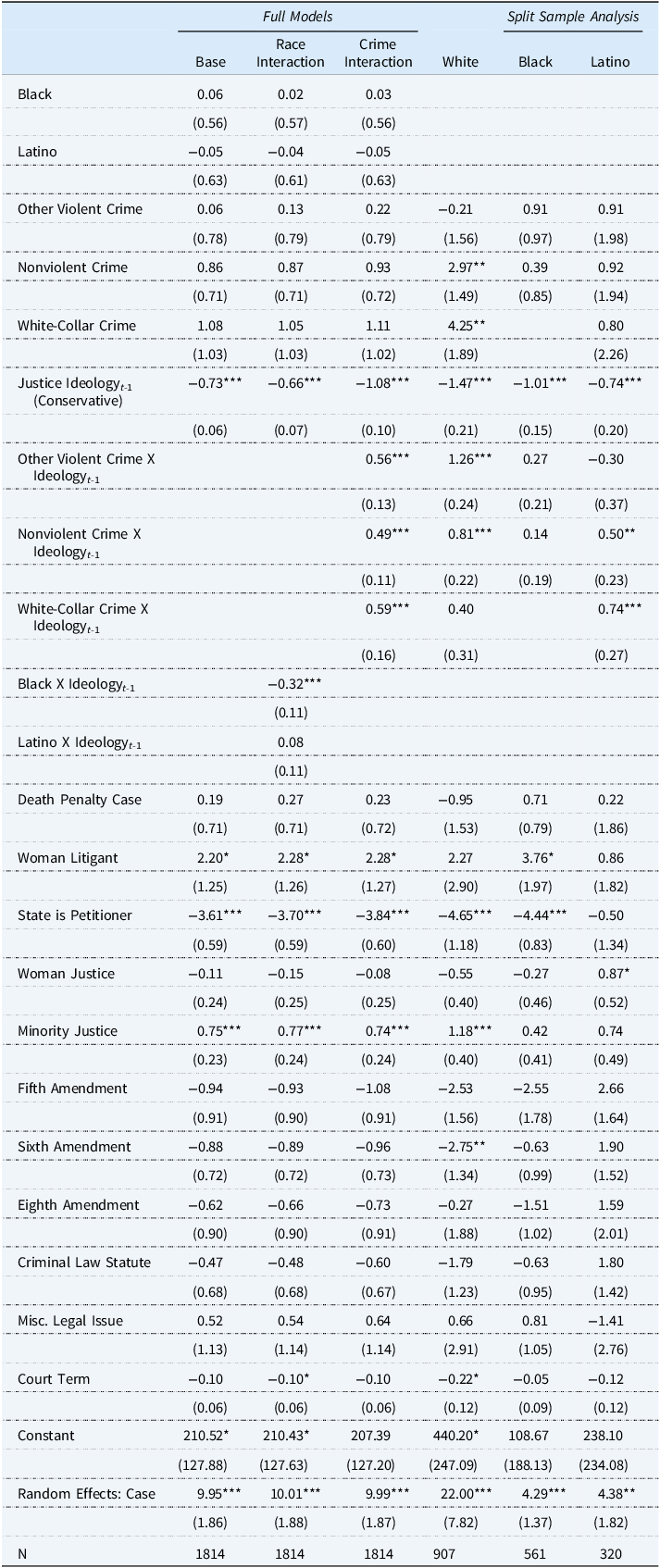

We present our findings in Table 1. Model 1, which excludes interaction terms, tests our first two hypotheses—that justices will be more likely to vote for white litigants and nonviolent offenders. Models 2 and 3 examine whether conservative and liberal justices respond differently to a litigant’s race and crime. In all models, the base category for race is white, and the reference category for crime is murder.

Table 1. Justice-Case Level Models

Note: Models estimated using multilevel-logistic regression with random effects by case. * p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

We find no support for our first two hypotheses that justices are less likely to vote for nonwhite and violent litigants. In Model 1, none of the litigant identity variables are statistically significant. There is no difference in the likelihood of justices voting for Black, Latino, or white litigants. And there is no difference in the likelihood of justices voting based on crime. Justice ideology has a negative, statistically significant effect, meaning that conservative justices are more likely to side with the State. However, if our third hypothesis is correct, the null effects are unsurprising.

We next examine the interaction between justice ideology and defendant race. Model 2 shows no direct effects of race or crime type. Justice ideology has a negative, statistically significant direct effect, suggesting that conservative justices are more likely to side with the State, at least when the defendant is white. Turning to the interaction terms, we find support for our third hypothesis. The negative and statistically significant interaction between justice ideology and Black litigant indicates that conservative justices are more likely to vote against Black respondents, reinforcing stereotypes that portray Black Americans as criminal.

Model 3, which interacts crime type and justice ideology, further supports our hypothesis. Although crime type does not exert a direct effect on justices’ votes, a statistically significant relationship between justice ideology and vote outcome emerges: conservative justices are more likely to vote against defendants accused of murder compared to their liberal counterparts. The positive and statistically significant interaction effect between justice ideology and both other violent crime and nonviolent crime indicate that a justices’ reactions to a defendant’s offense is contingent upon their ideology.

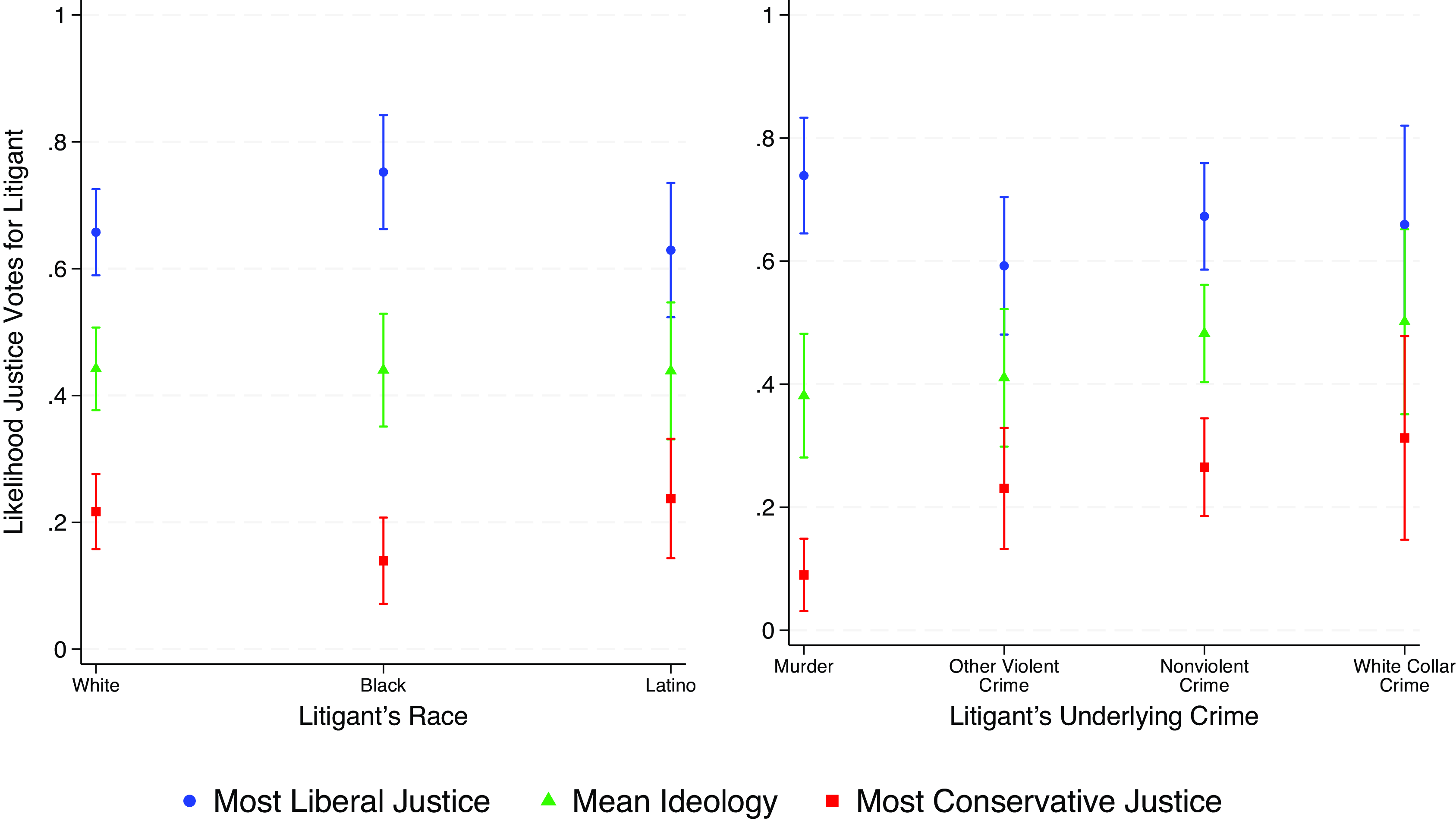

To further investigate these effects and ease interpretation of the interactions, Figure 1 displays the predicted probability of voting in favor of the litigant for the most liberal, most conservative justice, and mean ideological justice.Footnote 10 The figure on the left displays justices’ votes based on the defendant’s racial identity. Across all racial groups, the most liberal justice is more likely to vote for the litigant than either the average or most conservative justice. The most liberal justice has a 66% chance of voting for white litigants, a 75% chance of voting for Black litigants and a 63% likelihood of voting for Latino defendants. The most conservative justice’s likelihoods of voting for litigants are only 22% for white litigants, 14% for Black litigants and 24% for Latino defendants.

Figure 1. Predicted Probability of Voting for Litigant by Race, Crime, and Justice Ideology.

Two key observations stand out. First, among justices at the ideological extremes, the treatment of Black defendants deviates most markedly from that of white and Latino litigants, though these differences do not reach statistical significance. Second, the disparity in voting likelihood between liberal and conservative justices varies by litigant racial identity. Liberal justices are more likely to vote in favor of the litigant compared to their conservative colleagues, with the ideological gap being most pronounced for Black defendants—those most stereotypically associated with criminality. The confidence intervals for the voting behavior of the most liberal and conservative justices never overlap, indicating distinct treatment based on litigant racial identity. When comparing these extremes to the average justice, the confidence interval overlaps for the ideological extremes only in the case of Latinos defendants.

The criminal offense-based figure (right) reveals distinct differences for two of the four offense types: murder and nonviolent crimes. Across all categories, the most liberal justice is consistently more likely to vote for the litigant than the most conservative justice, but the gap varies by offense. Specifically, the most conservative justice has a 9% likelihood of voting for defendants who committed murder compared to 74% for the most liberal justice, while for nonviolent crimes the probabilities are 26% and 67%, respectively. For violent crimes, the most conservative and liberal justices’ confidence intervals do not overlap with each other but do overlap with the mean justice ideology. By contrast, for white-collar crimes, the confidences intervals for all ideological groups overlap, suggesting that ideology plays a diminished role in these cases, perhaps because liberal justices feel less compelled to counteract biases that favor stereotypically white crimes. Overall, this figure highlights a broader pattern, justices tend to vote for litigants by their racialized stereotypes, favoring litigants accused of white-collar crimes, followed by nonviolent and violent offenses. The most liberal justice does, however, depart from this trend by siding more with litigants accused of murder.

Other factors help explain justices’ votes. When the state is the petitioner, justices are less likely to vote for the litigant, meaning the state is more likely to win. Minority justices are more likely to vote in favor of litigants; however, this includes only Justices Sotomayor and Thomas, so we hesitate to read much into this finding.

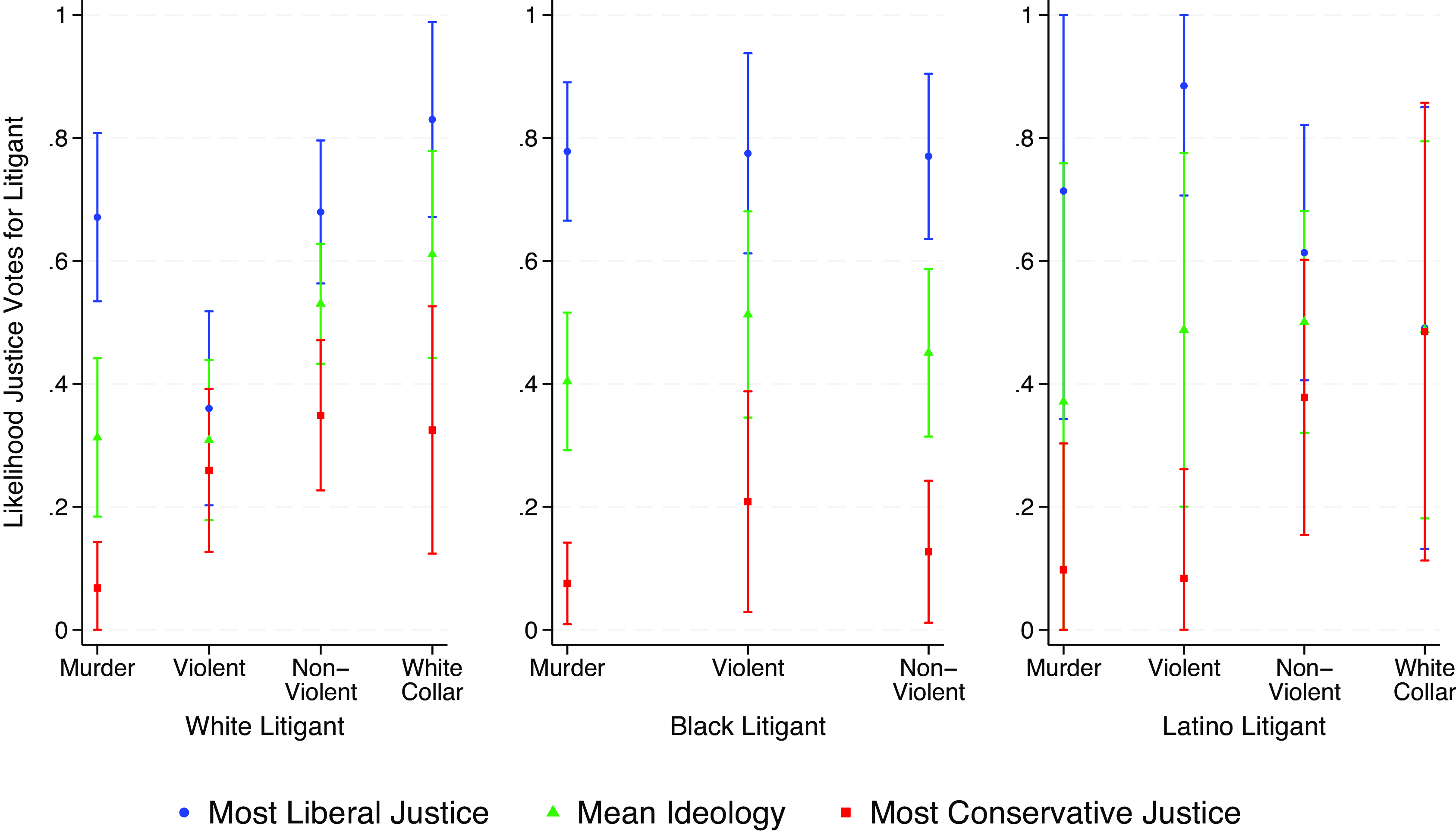

To further explore these trends, we create subsamples based on litigants’ racial identity. We do this to ease interpretation rather than create a three-way interaction between racial identity, crime, and justice ideology. These models allow us to examine whether the effect of justice ideology is specific to both litigant race and crime type. Here, too, the base category for race is white, and the reference category for crime is murder. Given how stereotypes about crime have been racialized, we expect stronger effects for nonwhite litigants charged with violent crimes.

Judicial ideology consistently exhibits a negative and statistically significant across the models, indicating conservative justices are less likely than their than liberal colleagues to vote for those charged with murder, regardless of litigant race. As before, the “state as petitioner” coefficient is negative and statistically significant, except for models limited to Latino litigants, suggesting that justices are less likely to vote for litigants when the state initiates the case. The positive effect of minority justices on litigant-favorable votes reaches significance only in the white-only model, and whites are less likely to receive favorable votes in cases concerning the Sixth Amendment.

In the split sample models, the influence of crime type on vote choice varies by racial group. For Black and Latino defendants, crime type does not affect vote choice directly. By contrast, for white defendants, those charged with nonviolent and white-collar offenses are more likely to receive favorable votes from justices whose ideology is moderate (ideology = 0). Additionally, when crime type is interacted with justice ideology, racial disparities appear. Among white defendants, the interactions between both violent and nonviolent crime and ideology are positive and statistically significant, indicating that conservative justices are more likely to vote for white litigants accused of violent and nonviolent crimes. Similarly, for Latino litigants, the interaction of nonviolent and white-collar crimes with ideology are also positive and significant. In contrast, for Black litigants, we find no statistically significant interactions, suggesting that justices’ votes for Black litigants are not influenced by crime type and ideology.

To ease interpretation, Figure 2 plots the predicted likelihood that a justice will vote for a litigant, disaggregated by race and offense type, across three ideological positions: most liberal, most conservative, and ideologically mean justice. The results show large differences based on race and crime type. Focusing on white defendants, the most liberal justice has a 68% probability of voting for litigants charged with nonviolent crimes and 67% likelihood of voting in favor of litigants charged with murder cases. Conversely, the most conservative justice supports white defendants accused of murder only 7% of the time, and those charged with nonviolent crimes 35% of the time.

Figure 2. Split Samples, Predicted Probability of Voting for Litigant.

In contrast, the most conservative justice provides minimal support for Black litigants across all crime types. Specifically, the predicted probability of support for Black defendants is 8% for murder, 21% for violent crimes, and 13% for non-violent crimes. By comparison, the most liberal justice is substantially more likely to vote for Black defendants, with predicted probabilities of 78% for murder, 78% for violent offense, and 77% for nonviolent crimes.

For Latino defendants, the most conservative justice is more likely to vote in their favor whey they are charged with white-collar (48%) or nonviolent crimes (38%), but far less likely to favor Latinos accused of murder (10%) or violent crimes (8%). In contrast, the most liberal justice is most likely to vote in favor of Latino litigants charged with violent crime (88%) or murder offenses (71%) and least likely to do so for white collar (49%) or nonviolent (61%) crimes. These findings suggest that conservative and liberal justices may agree more on case outcomes for lesser crimes but diverge more when adjudicating most serious offenses, particularly for Latino defendants.

The confidence intervals for the most liberal and conservative justices overlap in only three instances, suggesting significant differences in judicial behavior emerge in most cases. There is no statistically significant difference in how the most liberal and conservative justices treat Latinos charged with nonviolent or white-collar crimes, although it remains unclear whether this pattern would extend to Black defendants facing white-collar charges, as there were none in our sample. Similarly, it is not possible to determine how the most ideologically polarized justices would treat white litigants charged with other violent crimes. This limitation is due to two observed tendencies: the most conservative justices are substantially more likely to vote in favor of white violent offenders than nonwhite violent offenders (26% for white; 13% for Black; 8% for Latino), whereas the most liberal justice is significantly less likely to support white defendants relative to nonwhite defendants in violent crime cases (36% for white; 77% for Black; 88% for Latino). Notably, compared to their liberal colleagues, conservative justices consistently exhibit lower support for Black litigants, irrespective of crime type. Taken together, these results reveal justices’ voting behavior varies based on both the litigant’s race and the nature of the crime.

Justices’ Own Words

The quantitative analysis offers support for our third hypothesis that conservative and liberal justices vote based on a litigant’s race and crime. Yet racialized biases are not limited to votes; justices’ written opinions also reflect their biases. This is important because while votes decide who wins and loses, the language of the written decisions represents the law and guides future outcomes (Matthews Reference Matthews2022).

Written stereotypes and biases are difficult to measure, leading scholars to turn to text analysis. For example, in their examination of over one million U.S. court opinions, Rice et al. (Reference Rice, Rhodes and Nteta2019) find federal and state court judges exhibit implicit racial bias, showing that Black names are more often associated with negative terms while white names are frequently paired with pleasant concepts. Their findings demonstrate the need to look beyond easily quantified factors. However, this analysis still does not tell the full story. Beyond knowing how positive and negative terms are linked with litigants’ racial identities, it is important to explore how justices enforce racialized stereotypes in their writing. Here, we build on Rice et al. (Reference Rice, Rhodes and Nteta2019), offering evidence of bias in justices’ language—and its notable absence. We do not claim the passages we discuss are representative of all decisions nor that racial bias will appear in all decisions. A discussion of the case selection is available in the appendix. Instead, we offer these examples to illustrate how and when justices’ biases emerge in their opinions.

The justices invoke litigants’ racial identity and their offense in several ways. Often, justices treat race as inconsequential and ignore the context that gave rise to the crime. They do so by cloaking their decision in race-neutral legal justifications, as Lawrence (Reference Lawrence1987) expects. At times, justices explicitly invoke race and/or the underlying crime to explain why the defendant is unworthy of constitutional protections, often in ways that promote white racial hierarchy. Below, we present cases of three ways that racialized stereotypes about crime have entered justices’ written opinions: 1) Explicit discussions of race, 2) Implicit discussions of racialized crime, and 3) Explicit discussions linking a litigant’s race and crime.

Constructing Race: Davis v. Ayala; Padilla v. Kentucky; and District Attorney v. Osborne

Race can be an overt case element, and justices may directly confront racial issues. In Davis v. Ayala, race is central, yet the conservative majority ignores how race may have affected the outcome.Footnote 11 In Davis, the Court upheld Ayala’s, a Latino man, death sentence despite challenges during jury selection in which the prosecutor rejected all potential Black or Latino jurors. Ayala’s attorney objected to the exclusion of the prospective jurors. The trial judge hosted an in-chambers hearing that excluded Ayala and his attorney, during which the prosecutor offered non-racially motivated justifications. The trial court agreed with the prosecutor, and the all-white jury found Ayala guilty of murder and sentenced him to death. On appeal, the appellate court found excluding Ayala’s attorney from the hearing was erroneous. The U.S. Supreme Court’s majority decision, written by Justice Alito and joined by the conservative justices, ruled Ayala, and prisoners like him, are not entitled to relief unless the legal error resulted from “actual prejudice.” Here, the majority found the error to be “harmless.”

This case explicitly invokes race—a Latino defendant and racial/ethnic minority jurors, yet the majority ignores the effect race might have had on prospective jurors’ evaluations. Their opinion did not mention the litigant’s race, as ignoring it better allowed them to reach their preferred outcome. In contrast, the liberal justices explicitly discuss race and racism. Writing for the dissent, Justice Sotomayor notes the prosecutor’s racially-neutral justifications for juror expulsion may not have been credible and remarks that the person best able to testify to its credibility—Ayala’s attorney—was excluded from the meeting. She then compares qualities of two jurors—a white woman and a Black man—who have similar death penalty attitudes. Sotomayor accuses the majority of focusing on one “arguably ambiguous statement” to draw distinctions between the two in ways that overlook the role of racial bias. In this case, the majority defends the white juror while casting doubt on the Black juror. Liberal justices, who are more likely to acknowledge race’s role, explicitly mention race which the majority purposefully ignores.

Race is also at the forefront of Padilla v. Kentucky.Footnote 12 Jose Padilla, a Honduran immigrant, pled guilty to transporting marijuana, but his attorney never informed him that a guilty plea could lead to deportation. Concluding for a 7-2 Court, Justice Stevens writes “deportation is an integral part—indeed, sometimes the most important part—of the penalty that may be imposed on noncitizen defendants who plead guilty to specified crimes.” The majority determines that attorneys have a duty to advise non-citizens that pleading guilty may lead to deportation. The majority focuses on Padilla’s ethnicity. The opinion’s very first paragraph identifies Padilla as a native Honduran, lawful permanent resident for over 40 years, and a Vietnam War veteran. Stevens evokes Padilla’s ethnicity and immigration status as well as positively constructs Padilla as an upstanding individual worthy of equal treatment.

In dissent, Justice Scalia, joined by Thomas, ignores all case context. The word immigration appears only once, and the dissenting justices do not acknowledge Padilla’s military service, which they champion in other cases. They sidestep these factors, focusing exclusively on the Sixth Amendment. Their focus on the law illustrates how race-neutral language justifies decisions that harm marginalized litigants. “In the best of all possible worlds,” Scalia writes, “criminal defendants contemplating a guilty plea ought to be advised of all serious collateral consequences of conviction … The Constitution, however, is not an all-purpose tool for judicial construction of a perfect world.” With this, Justices Scalia and Thomas treat Padilla and all immigrants as undeserving of the full protection of the law.

In another example, conservative justices invoke race to dramatize the crime while denying the perpetrator’s humanity. In District Attorney’s Office for the Third Judicial District v. Osborne, William Osborne, a Black man, was convicted of sexual assault, assault, and kidnapping.Footnote 13 Before the trial, the state performed a basic and preliminary DNA test, which found a genotype that matched Osborne’s blood sample but eliminated his co-defendants. Osborne asked for more tests, to no avail. Post-conviction, Osborne again requested access to the state’s DNA evidence. In a 5-4 conservative majority opinion, the justices held that defendants do not have a constitutional right to access the state’s DNA evidence used against them at trial. Chief Justice Roberts’s majority opinion goes into gruesome detail about the original attack. In a concurrence, Justice Alito further constructs Osborne as a criminal attempting to “game the system” and implies the defendant is likely a liar.

Writing for the dissent, Justice Stevens notes the state has evidence that could confirm either that justice has been served or that Osborne is innocent. “Yet for reasons the State has been unable or unwilling to articulate, it refuses to allow Osborne to test the evidence at his own expense and to thereby ascertain the truth once and for all.” Only the liberal justices view Osborne as a person deserving justice, while the conservative majority paint a picture of an immoral, dangerous man. Washing their hands of Osborne, the majority claims it’s not their responsibility to help but the state legislature’s job to determine whether criminals like Osborne deserve DNA evidence at trial. Unlike the other examples where conservative justices ignore a case’s context, the conservative justices dive fully into the case’s details, using context only when beneficial.

Constructing Crime: Begay v. U.S. and Brumfield v. Cain

Our quantitative analysis finds conservative justices are less likely to vote for defendants who commit murder and other violent offenses—crimes stereotyped as nonwhite. Conservative justices’ contempt for these defendants is apparent in their characterization of the underlying crimes in their decisions and in their focus on the crime rather than legal justifications. We discuss two examples of justices’ opinions centered on the underlying offense.

In Begay v. U.S., the Court decided whether previous convictions for driving while intoxicated qualified as violent felonies under a federal career criminal law.Footnote 14 Larry Begay, a Navajo man, pleaded guilty to firearm possession when he attempted to shoot his sister one night after drinking heavily. Begay had twelve previous convictions of driving while intoxicated, and his plea triggered a 15-year mandatory minimum sentence. The majority and dissenting opinions present divergent perspectives of Begay’s underlying crime—firearm possession—and its circumstances. Writing for the 6-3 majority, Justice Breyer defined the crime and Begay’s actions succinctly: Begay “threatened his sister and aunt with a rifle. The police arrested him. Begay admitted he was a felon and pleaded guilty to a federal charge of unlawful possession of a firearm.” Conversely, Justice Alito’s dissent offers a dramatic narrative, painting Begay as extremely dangerous. He begins, “after a night of heavy drinking, [Begay] pointed a rifle at his aunt and threatened to shoot if she did not give him money. When she replied she did not have any money, [Begay] repeatedly pulled the trigger, but the rifle was unloaded and did not fire. [Begay] then threated his sister in a similar fashion.” There is no question of Begay’s prior felonies; in fact, he pleaded guilty to the possession charge and did not dispute his prior convictions. The only question was whether his previous intoxicated driving offenses constituted “violent” felonies. Alito’s excessive retelling of the night provides no answer to that question. Instead, it characterizes the defendant’s actions as vicious and portrays Begay as unworthy of legal protections.

In other cases, justices focus on the consequences of a crime to deny humanity for a defendant of color. Brumfield v. Cain focuses on the rights of an intellectually disabled man convicted of murder.Footnote 15 In 1993, Kevan Brumfield, a Black man, and another person murdered Betty Smothers, a Black off-duty police officer. Brumfield does not dispute these facts but believes he was denied a proper post-trial hearing. Following the Court’s decision that the Eighth Amendment prohibits executions of the intellectually disabled, Brumfield challenged the sentencing phase of his trial, which had prevented him from proving his mental impairment. Justice Sotomayor’s 5-4 majority opinion focuses on the trial court’s failure to grant Brumfield a hearing, despite evidence suggesting Brumfield had an intellectual disability.

Writing for the dissent, Justice Thomas valorizes the victim and her family while offering a scathing condemnation of Brumfield. Thomas begins, “This case is a study in contrasts. On the one hand, we have Kevan Brumfield, a man who murdered Louisiana police officer Betty Smothers and who has spent the last 20 years claiming his actions were the product of circumstances beyond his control.” Referring to the victim deferentially as Corporal Smothers throughout, Thomas then contrasts Brumfield with Smothers’s son. Thomas continues, “On the other hand, we have Warrick Dunn, the eldest son of Corporal Smothers, who responded to circumstances beyond his control by caring for his family, building a professional football career, and turning his success on the field into charitable work off the field.” The victim’s son is not relevant. However, Thomas uses Dunn, notably another Black man, to argue that “circumstances outside one’s control” should not be considered for Brumfield. Thomas openly shows contempt for Brumfield and implies that race plays no role in individuals’ life experiences. After all, if Dunn can overcome extraordinary circumstances, Brumfield should have as well. Thomas highlights Warwick Dunn’s football career, noting “during [Dunn’s] time at Florida State, he set records on the field while coping with the loss of his mother.” With these anecdotes, Thomas focuses on Dunn’s “racial exceptionalism,” indicating individuals, like Brumfield, who do not fit this mold are undeserving (Carbado and Gulati Reference Carbado and Gulati2013, 31). While the other dissenting justices, Alito, Roberts, and Scalia, disagreed with the nature of Thomas’s discussion of Smothers’s son, they still signed on to Thomas’s opinion.

Constructing Race and Crime: Boumediene v. Bush

In our last example, the Court expressly invokes race and nationality amid the context of war, offering a stark split in how liberals and conservatives view war-time criminals. At its core, Boumediene v. Bush is a separation of powers case concerning procedural protections for war-time prisoners.Footnote 16 With swing vote Justice Kennedy writing the opinion, the 5-4 majority of liberal justices held that Guantanamo Bay detainees are entitled to pre-trial habeas corpus hearings. The majority begins with a brief description of the defendants, “Petitioners are aliens designated as enemy combatants and detained at the United States Naval Station at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.” The only other significant details the majority includes about the petitioners is their apprehension location and that the petitioners deny being members of al Qaeda or the Taliban. The majority focuses on the larger separation of powers issues and the procedural protections enemy combatants are due.

In contrast, Justice Scalia views these issues through a racialized and nationalized lens. His dissent contextualizes the case, “America is at war with radical Islamists. The enemy began by killing Americans and American allies abroad,” reporting specific numbers and locations in which people were killed. This is a serious threat, he says, which the Court does not comprehend. He warns that enemy combatants aren’t done killing and offers evidence of previous detainees who did just that. By focusing on the actions of some detainees and situating those actions in the context of multiple wars, Scalia strips the detainees of their humanity and turns them into weapons of war not deserving of rights. Unlike our other examples where the criminalizing of racial groups is done more subtly, here, Scalia explicitly constructs individuals of Middle Eastern descent or Muslim religious faith as criminal and anti-American.

Discussion & Conclusion

The widespread belief that justices apply laws impartially may not tell the full story of Supreme Court decisionmaking. Two overlooked but powerful factors—prejudice and the stereotypes that sustain it—also shape justices’ decisionmaking. Our results show Supreme Court justices’ prejudices affect their votes and opinions, calling into question the assumption of purely objective judicial reasoning.

We argued the Supreme Court, a historically white institution, plays a powerful role in perpetuating racial stereotypes and investigated how the Court invokes race in its votes and written opinions by analyzing how justices use crime as a racial cue. As others have found (Eberhardt et al. Reference Eberhardt, Atiba Goff, Purdie and Davies2004), we argue when justices think of crime, they think of non-white defendants, and when they think of non-white defendants, they assume criminal guilt and vote accordingly. Thus, the Court criminalizes non-white defendants, even when uncertain of a defendant’s race.

Our quantitative results show evidence of racial inequalities in the Court’s decisions. Justices do not treat all criminal defendants equally; rather the litigant’s race, crime and the justice’s ideology affect their votes. Justices are consistent in their behavior—with liberal justices in general being more favorable to nonwhite litigants and conservative justices showing more variability in their behavior based on litigant race. Conservative justices are more likely than their liberal counterparts to vote against nonwhite defendants and violent offenders, a minority-coded offense. With this evidence alone, we should be concerned about how the Court treats certain defendants.

While some studies find evidence of racial bias, such biases are often influenced by judicial ideology, which seems to be the overwhelming driver of judicial decision making in the context of criminal procedure (see e.g., Harris and Sen Reference Harris and Sen2019). Our findings suggest that the judge’s race matters less than their ideology and the defendant’s racial and criminal stereotypes, two important variables not often accounted for. This is especially troubling, given that federal courts have often been viewed as a champion of civil rights and racial equality. But if justices’ decisions are swayed by racial bias and political ideology, this will be less advantageous for litigants of color.

The analysis of the written decisions lifts the veil of race neutrality by showing how justices reinforce racialized criminal stereotypes. At times, justices ignore race, offering “neutral” legal justifications which reinforce racial categorization and maintain a hierarchy that benefits whites at the expense of people of color. At other moments, justices directly incorporate race in their opinions. This occurs when race-neutral rationales do not lead to their preferred outcome. For instance, when Justice Scalia described the defendants in Boumediene as “radical Islamists,” he was on the losing side.

In most of the examples we present, the bias is subtler. Justices discuss extraneous facts and build dramatic narratives reinforcing white racial ideology. We saw this when Justice Thomas discussed how one Black man faced adversity with exceptional outcomes, while entirely dismissing how life circumstances affected another Black man. In these ways, the justices reinforce who deserves punishment and who does not, at the same time drawing distinctions within racial/ethnic minority groups, implying that only those without faults are worthy of just treatment. Finding these results at the Supreme Court, which has the most visibility of all the courts in the federal judicial system, is troubling. We suspect this is true in the lower courts and may be even more pronounced as there is less public oversight. Further research into these courts would shed valuable insight into these concerns.

As previous research has shown, we too find the law is not colorblind. Instead, ostensibly race-neutral decisionmaking obscures underlying discrimination. However, there are reasons for cautious optimism. As courts diversify, the inclusion of new perspectives may drive changes in court outcomes and influence colleagues to recognize and address biases. For instance, studies have demonstrated that when black judges are added to all-white appellate court panels, they shift the votes of their white colleagues toward more favorable outcomes for minority plaintiffs or more liberal directions, particularly in cases where race is salient (Cox and Miles Reference Cox and Miles2008, Kastellec Reference Kastellec2013). Even at the trial court level, when judges work independently, there is evidence that an increase in Black judges leads to more equitable sentencing for both Black and white defendants (Harris Reference Harris2024).

Unfortunately, our data cannot pinpoint the source of the justices’ bias, particularly regarding the language used in their decisions. Even if justices borrow language from attorneys’ briefs (Corley Reference Corley2008), their choice to adopt prejudicial language constitutes an implicit endorsement of that bias. Nevertheless, further research is needed to explore whether this bias stems primarily from the justices themselves, from attorneys’ briefs, or from a confluence of these and other factors, and whether the justices modify such language before finalizing opinions. Regardless of its origins, our findings indicate that the Court continues to shape societal understandings of who is “criminal” and who is “nonwhite,” underscoring the profound influence of judicial decisionmaking on racial narratives in the United States.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2025.10010

Data availability statement

The data and code to replicating all analyses in this article and online appendix are available on Harvard Dataverse Network, at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/AVCBEI.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the editor and reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions. They would also like to thank those who provided important feedback along the way, including fellow panelists at the 2022 APSA and 2023 SPSA. Finally, we wish to thank Elizabeth Maltby’s father, Marc, for his part in the initial data collection and proving that no one is too senior to be drafted into unpaid research labor by their children.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific financial support.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.